Google celebrates legendary British composer and opera singer, Amanda Aldridge, with Doodle

17 June 2022, 12:14 | Updated: 20 June 2022, 11:47

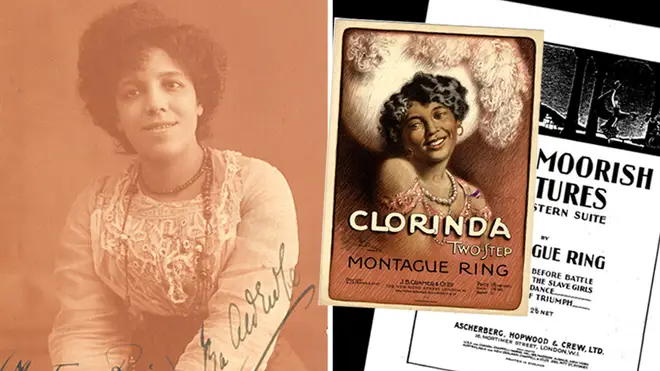

Today’s Google Doodle celebrates Amanda Aldridge who, under the pseudonym of Montague Ring, was an extraordinarily successful composer and teacher in her day. We explore her key works, and what happened to the parlour song as a genre.

Here’s the story of Amanda Aldridge, who is being celebrated in a special Google Doodle.

In 1921, the influential American activist and scholar, W. E. B. Du Bois invited an African-British composer, teacher and singer to appear at the Second Pan-African Congress addressing issues facing Africa as a result of European colonialism.

She had to turn down the prestigious event as she was caring for her very ill sister, who was a talented contralto singer.

The composer in question was Amanda Aldridge, a prolific composer of Romantic parlour songs, and teacher of singers and composers.

“As you know, my sister is very helpless… I cannot leave for more than a few minutes at a time,” was Aldridge’s response to Du Bois. Her sister, Luranah Aldridge sadly took her own life 10 years later.

The legacy of the Aldridge family is far-reaching, fascinating and inspiring. So, who was Amanda Aldridge, and why don’t we all know her name today? Here’s everything you need to know about the composer and teacher.

See Amanda Aldridge Google Doodle >

Lazy Dance (La Paresseuse), Montague Ring; River Raisin Ragtime Revue

Who was Amanda Aldridge?

Amanda Aldridge (1866-1956) was a British opera singer, teacher and composer who worked under the pseudonym Montague Ring, in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Her father was a well-known Shakespeare actor, the African-American Ira Aldridge, who was dubbed the ‘African Roscius’ when he first starred as Othello at the Royalty Theatre in London, in 1825.

Her mother was Swede Amanda Brandt, her sisters Rachael and the star operatic contralto Luranah Aldridge, who nearly made history as the first performer of African heritage to star at Bayreuth Opera House, before illness forced her to cancel. They also had brothers, Ira Daniel Aldridge and Ira Frederick, a pianist. They both died tragically young like their sister Luranah.

Amanda Aldridge studied composition and singing at Royal College of Music with Jenny Lind, who was famously portrayed in musical film The Greatest Showman, and Frederick Bridge among others.

Read more: Meet Jenny Lind, the real-life opera singer in The Greatest Showman

Red Velvet | Adrian Lester on the true story of Ira Aldridge

Amanda Aldridge – an influential composer and teacher

Aldridge pursued both performing and composing until laryngitis led to a throat injury that cut her vocal career short. She dedicated herself to teaching – with lyric tenor Roland Hayes and singer, pianist and composer Lawrence Benjamin Brown among her esteemed students – and composition, so ended up leaving quite the legacy in the British music scene and African-British circles in London.

Aldridge’s contribution to parlour music, under the pseudonym Montague Ring, was inspiringly influential. She wrote over thirty songs and dozens of pieces of instrumental music. They were popular in style, and merged different rhythmic influences and genres, selling big and delighting myriad households.

Her works include Three Arabian Dances, Lazy Dance (watch above), and songs like ‘Little Southern Love Song’ and ‘Little Missie Cakewalk’.

Read more: Meet Nadia Boulanger, the teacher behind the 20th century’s greatest composers

Chineke! Orchestra - Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Ballade for orchestra, Op.33

Many of Aldridge’s songs helped her explore her half African-American heritage, something her mentor Jenny Lind encouraged. Her involvement with the African-British community in London included a friendship with the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and his family.

“She sang Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s songs and was friends with his daughter Avril,” mezzo-soprano and author Patricia Hammond tells Classic FM. “She taught singing and diction to some of the most legendary African-British, British-Caribbean and African-American figures in music and drama, including Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson and Lawrence Benjamin Brown.”

Hammond adds: “She not only taught them but was extremely generous in providing introductions and keeping a community of support going.”

Aldridge set two poems by the legendary African-American writer Paul Laurence Dunbar as songs, ‘Summah is de Lovin’ Time’ and ‘Tis Morning’, and composed Three African Dances for piano, which was probably her best-known work during her lifetime.

Read more: Who was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor ? Meet the brilliant English composer

Little Missie Cakewalk - Amanda Aldridge (Montague Ring) 1908

What is a parlour song?

The best thing about parlour songs, for mezzo Patricia Hammond, is their “instant humanity”.

“The fact that they wear their heart on the outside,” she explains. “These are songs that are designed to include people, to share among friends. Memorable tunes. I remember an outspoken lady once in an audience sitting next to me who said ‘I want something mellifluous!’ These are mellifluous.”

Parlour songs were popular songs, usually for voice and piano accompaniment, designed for use and enjoyment in living rooms, often written so as not to be too virtuosic. This enabled amateur and professional musicians alike to perform them.

As well as Aldridge, many women were prolific in the parlour song genre – including May Brahe, Amy Woodforde-Finden, Carrie Jacobs-Bond and Charlotte Alington Barnard.

“The success of the ballads of Charlotte Alington Barnard (“Claribel”) in the 1860s was so astonishing that rival publishers vied with each other to insult her in print, claiming that the ease with which her works could be played and sung at home, as well as their catchiness, caused a degradation of public taste,” Patricia Hammond writes.

Read more: 27 pop songs you didn’t know were inspired by classical pieces

Azalea - Amanda Aldridge (Montague Ring) 1907

Why don’t we hear more parlour songs today?

The ‘amateur’ aim of the songs seems to have relegated them to the bottom of the pile in music history.

Even though ‘amateur’, in its truest sense, evokes ‘passion’ (think of the French term for love, ‘amour’, that it’s derived from), it brings with it non-serious connotations. And considering women’s position in society in the 19th and early 20th century, it was a genre they could flourish in while the more ‘serious’ professional genres deemed suitable for public life remained out of bounds.

“It’s only speculation, but I feel there was a moment, in around the 1950s, when classical music became almost like a stately home, no longer lived in but supported and preserved, so concerts started to be curated rather than thrown together,” singer and parlour song enthusiast Patricia Hammond reflects.

“Before, people were more likely to just perform music they loved. If you look at concert programmes from the 1910s and 20s, there’d be glorious mixtures that put tangos and operetta in the company of Mozart as well as [parlour song composer] Carrie Jacobs-Bond.

“But with critics becoming gatekeepers to what is and isn’t worthy of a concert series, the warmth and directness of these parlour songs didn’t seem to have a place amongst the lofty utterances of their favourite Lieder, and composers who had proved their grandeur by also writing symphonies.”

Click here to listen to our ‘Calm Piano’ playlist on Global Player, our mobile app >

Warren Mailey-Smith plays Chopin's 'Minute' Waltz

What is the difference between parlour music and salon music?

While parlour songs and pieces were written for popularity, relative ease of performance, and amateur music-making in the home, works described as ‘salon’ music, by definition, were composed for more public-facing performances, albeit still in the living room.

Salons were gatherings of people around an inspiring host – think of Gertrude Stein in Paris – and the music it required, or inspired, was likely heard by more people at one sitting than the everyday parlour song. Composers like Chopin and Franz Behr are known for writing salon music, and Chopin’s salon music especially – thinking to his virtuosic preludes, nocturnes and waltzes – is a secure staple in the classical music canon, heard prolifically in concert halls and on the radio.

Hammond has spent a lot of time performing, exploring and writing about the genre. We ask her if the relative neglect of parlour songs will change any time soon, and if they might join salon music in being heard more in concert halls one day.

“I do believe that these Parlour songs are due a revival soon,” she says. “But I believe that not enough time has elapsed yet.”

And she reminds us: “Madrigals fell out of favour before they were given a major revival in the 1920s. Even Bach had to be revived by Mendelssohn, 80 years after Bach’s death.

“Maybe time was needed to forget the stuffy church services Bach’s works were written for, and to forget the post-prandial disarray that madrigals were performed over.”

We look forward to hopefully seeing these works by fascinating women dusted off before too long.

Patricia Hammond’s book, She Wrote The Songs, is out now in Valley Press. Click here to find out more.