On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

11 May 2021, 16:24

One scale that goes from C to B, with five equivalent flats and sharps in between, makes up pretty much all the melodies in Western music – but how did we get to these 12 notes?

All melodies and harmony in Western music is typically built from just 12 notes.

Whether it’s a sumptuous symphony, flourishing concerto or your favourite song, it will contain 12 familiar tones – and be based around familiar intervals between these tones – identified, honed and relied on throughout Western music history to create the melodies we know and love today.

But why just 12 notes? Why don’t we use more, and how can the awe-inspiring depth and breadth of music we’ve been gifted come from so limited a collection of sounds? All will be revealed, so do read on…

Read more: Why do pianos have 88 keys?

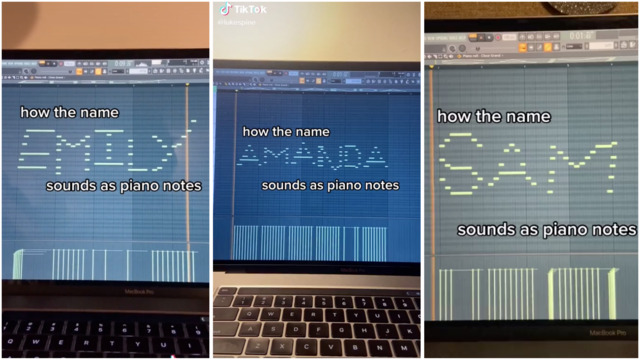

TikTok composer Luke Spine is setting names to piano music

Western music typically uses 12 notes – C, D, E, F, G, A and B, plus five flats and equivalent sharps in between, which are: C sharp/D flat (they’re the same note, just named differently depending on what key signature is being used), D sharp/E flat, F sharp/G flat, G sharp/A flat and A sharp/B flat.

So the final order of the 12-note chromatic scale, going upwards, is C, C sharp/D flat, D, D sharp/E flat, E, F F sharp/G flat, G, G sharp/A flat, A, A sharp/B flat, and B (see image above).

Click here to listen to the Classic FM Hall of Fame 2021 playlist on Global Player

These 12 notes have typically been used to compose most of the Western music we listen to. The reasons music has landed on these specific notes can be summed up as a convergence of convenience, science and listener preferences.

And – how we split up an ‘octave’. So, how do we get that?

All sounds are the result of waves, and the frequency of waves determine the pitch of sounds we hear. Pitches or notes that sound high, for instance, have a high frequency. But when it comes to our familiar 12 notes, it’s not all about frequency – in fact, frequency hasn’t created this set of 12.

We typically use just 12 notes in Western music because of the spaces – or intervals – between the notes.

Pieces of music are familiar entirely because of these intervals. Think of the children’s song ‘Baa baa Black Sheep’ – it’s still the same ‘Baa baa Black sheep’ when you start on the note C as if you start on B, or indeed if it’s sung by a person with a deep, low voice as if it’s sung by a person with a very high voice. For performers and music theory buffs, this is what ‘transposing’ is.

Read more: What are modes and how do I use them?

Hans Zimmer's Ringtone Story | Colourful Future

Certain intervals typically sound better – or rather more harmonious; natural; matching – to the human ear than others.

The most harmonious interval between notes we hear is the octave, i.e. two tones played eight notes apart. In what is known as ‘octave equivalence’, notes that are eight tones apart have the same name, and roughly sound ‘the same’ to the human ear, but just in higher or lower versions.

Scientifically, there’s harmoniousness too: to produce a note an octave above one at 220 Hz, you simply double it to 440 Hz. It all fits together like a rather convenient musical maths puzzle.

Four cellists play Ravel’s Bolero on just one instrument

Most tuning systems around the world tend to prioritise building music around this most pleasing octave interval. And once we have this octave, it’s about how we divide that up. And that divide in Western music is prioritised around those intervals that are ‘harmonious’ like the octave.

The next most pleasing intervals are the perfect fifth and the perfect fourth. Most Western melodies are built around a journey between these octave, perfect fourth and perfect fifth interval relationships.

Other intervals that typically sound pleasing, safe and resolved to the human ear are major and minor thirds, and major and minor sixths. All music with these intervals sounds ‘harmonious’ and pleasing, rather than dissonant and jarring.

The dissonant intervals are minor and major seconds (also called tones and semitones) and major and minor sevenths. Two notes right next to each other, played together, are difficult to listen to – and it’s with these spaces that composers add the occasional shade of dissonance to juxtapose the light of harmonious sounds. It builds the tension and release that is vital for making music catchy and engaging to listen to.

If a piece has only harmonious intervals, it will sound pleasant but nothing much more. Ask Beethoven – he was the absolute master of meeting dissonance with harmony to create an irresistible and enduring body of melodies.

So that, in a nutshell, is how we landed on our 12 notes – a mix of enough intervals that are harmonious and pleasing, with just one or two more tense intervals to add a sprinkle of colour.

Read more: Classic FM’s glossary of useful musical terms

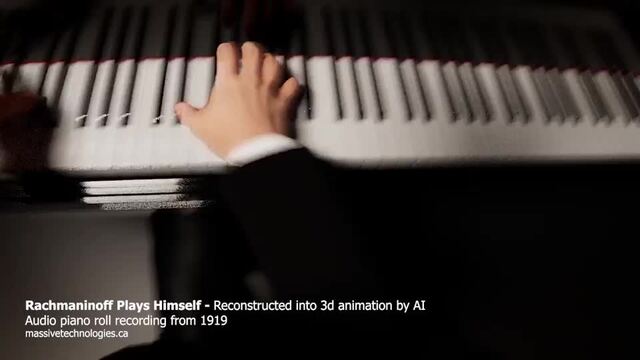

This AI has reconstructed actual Rachmaninov playing his own piano piece

More than 12 notes exist in actual sound waves, and these are most commonly explored in what is called ‘microtonal’ music – music that uses the notes in between the notes.

If the 12 notes of the typical scale exist due to intervals, and how we’re dividing the octave we’ve talked about, it’s a case of finding a new way to divide that octave to find alternative pitches. There are Western composers that have done this, including Ivan Wyschnegradsky who created 24 notes between one note and the octave above, and Harry Partch who tore up the rule book and composed 43 different notes within the octave.

The catch with microtonal music, and music that explores adding extra notes with uneven intervals, is it tends to sound less pleasing to the ear due to its containing more intervals that aren’t our pleasing perfect fifth and perfect fourth (see above).

The melodies and harmonies microtones build can sound too dissonant, so they don’t tend to catch on widely.

Notes outside the typical 12 can of course also be accessed by instruments that don’t rely on a set of keys, for example violins and trombones. And out-of-tune playing, of course!

Read more: Alto saxophonist shares his astonishing trick for playing 128 notes in an octave

Bastille's Dan Smith on combining pop songs with a classical orchestra

Yep, the same 12 notes. Western popular genres tend to use the same notes and intervals we hear in classical music.

Some popular genres have artists that experiment with microtonalism, and using the ‘notes between the notes’, with Australian psychedelic rock band King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard and British singer-songwriter Dua Lipa being among those who have done so successfully.

Talking about 12 notes in music generally applies to music from the West and from some other parts of the world, but certainly isn’t an exhaustive system for all music.

Arabic music had a 17-tone scale from around the thirteenth century, with the modern Arabic tone system now dividing the octave into 24, instead of 12 notes.

And Indian classical music, including raga, creates colour between notes far beyond the limited 12 notes heard in Western music. Indonesian gamelan also uses a different scale.

And there are of course many, many more diverse ways music-makers have ‘split the octave’ up into different notes to create sensational melodies throughout human history.