‘Classical music thrives on people coming together’ – composer Matthew Rooke

9 March 2021, 10:58 | Updated: 9 March 2021, 17:44

The British composer on twelve months since coronavirus cancelled everything, representation in classical music, and how we can rebuild for a brighter future.

“Classical music thrives on people coming together to create music, and then having others join them in sharing it through public performance,” composer Matthew Rooke tells Classic FM.

“This is the very sort of thing of course which is ideal for spreading a virus that depends on human interactions, so of course it all had to stop,” the composer says, as we catch up about the past year and its staggering impact on music.

The last twelve months, defined by the coronavirus pandemic, have changed music and left a lot of uncertainties for those making it and working in it.

“2020, and now 2021, has been like living through a very sector-specific nightmare,” Rooke reflects. “It has been like one of those sci-fi films where a whole world has been transformed or destroyed in an instant.”

He points out that, while the government has been good at safeguarding the buildings needed for performance once it can go ahead again, it hasn’t necessarily found a way to support every individual making the music and theatre we all love.

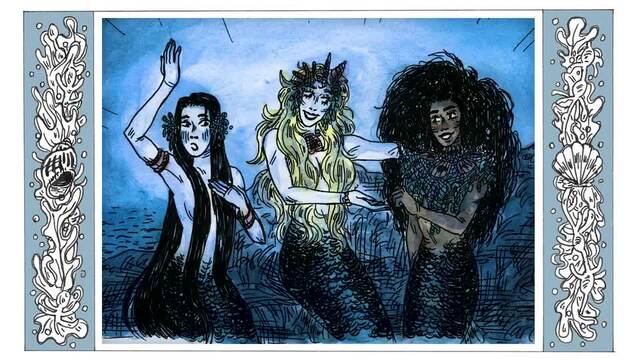

Matthew Rooke: I See Mermaids

‘Classical music thrives on people coming together’

Rooke is an English composer of Scottish-Gabonese descent, whose work spans composition and performance, and producing and directing for theatre. He’s worked with legendary composer John Tavener and the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland, as well as multimedia artist Billy Childish, guitarist Nitin Sawhney and violinist Ric Sanders.

Equally at home in the jazz world, Rooke’s career has also seen him crossing paths with Fred Thelonious Baker and The James Taylor Quartet.

His orchestral music ranges from scores and re-orchestrations for opera, to programmatic music aimed at young listeners (hear Rooke’s piece I see Mermaids, above).

Read more: ‘On the brink of devastation’: UK creative industries projected to lose 400,000 jobs >

Let Music Live protest on London's Parliament Square

“I hope that people fully appreciate what we lost as a result of this dreadful pandemic, not only in terms of dreadful number of lives lost, but also what we lost in terms of culture and our capacity to share things together.

“We are a social species and the loss of that opportunity to mix and share with others diminished us all,” the composer says.

“I hope this experience has crystallised what we must do to change to ensure that we avoid the horror stories that we have heard to date. And that the industry will start behaving like any other industry that is committed to a healthy future, by using this hiatus to really think through what needs to be changed and making significant investments in securing a broader based, more dynamic and socially-engaged future.”

Read more: Nearly 70 percent of primary schools have reduced music teaching because of COVID-19 >

Anthony McGill performs 'You have the right to remain silent' with Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra

‘It is rare to find open prejudice amongst singers, instrumentalists and composers’

2020 was dominated by issues of race and representation, too, following the death of George Floyd in May. Looking back on the year, we discuss race in relation to classical music.

“In my experience, it is rare to find open prejudice amongst singers, instrumentalists and composers,” Rooke says. “I believe, in part, it is that everyone has been through a very similar process of hard work, dedication, hours of gruelling practice and, to be honest, a lot of rejections along the way.”

He adds: “My generation and those coming through after me have benefited from the ground-breaking work of people like Willard White, Leontyne Price, and Jessye Norman, all of whom met and surpassed considerable challenges.”

But where musicians may have empathy and be champions of equality, classical music institutions as a whole remain less representative.

‘The classical music industry has fallen behind wider society’

“The classical music industry has fallen behind wider society,” Rooke says. “There are areas such as class, racial background and gender where the classical music industry does not look like it reflects the wider community that is paying for it.

“Whilst there are issues about fairness, the reality is that history is littered with enterprises that failed to nurture future talent and failed to develop new audiences to sustain themselves and grow in the future.”

Rooke also points out that there are still many people who love classical music – “we know this from audience figures for broadcasts and recordings” – but who wouldn’t set foot in a concert hall, perhaps because of their perceptions about who live music in formal halls is for.

He also points out that “the reality today for any Black singer, once they step outside of an opera house or concert hall, is that they will be faced with the same unacceptably high odds of serious jeopardy in terms of police mistreatment, quality of public services and access to other aspects of our public life as any other Black person.”

Classical music isn’t racist, insists Sheku Kanneh-Mason

So, how can classical music get better at welcoming all music lovers, while representing the diversity of the people it serves?

“I can’t think of a single major orchestra or opera company management in the UK led by a Black person or with a Black artistic leader,” Rooke reflects, naming Chineke! Orchestra, which was founded to provide career opportunities for Black, Asian and ethnically diverse classical musicians, as an exception.

“The problem for the industry is that the socio-economic, racial and gender profile of the people who are in control as a whole, in terms of boards and senior positions, is often less diverse than its workforce and, as a result, may not be naturally fully equipped to rise to these challenges and opportunities.”

Read more: Chi-chi Nwanoku: ‘Classical music is suddenly going to become much more diverse’ >

What can classical music do to increase representation?

To redress a balance, and have leaders in the arts that represent society, Rooke suggests classical music institutions look within and ask the difficult questions. He also points out how crucial bolstering classical music in state schools is so it doesn’t become “the preserve of those who can afford it” but rather those “who could benefit from it”.

And it’s of course vital to create “access to decent quality instruments and tuition” which are both very expensive factors and potential barriers when it comes to embarking on the classical music journey, Rooke says.

“Thankfully, orchestras and opera companies are not alone,” the composer says, sounding an optimistic note. “There are many others who have recognised these challenges before them and are likely to be willing to share their experiences.”

“To change things is a threefold process. It involves fully understanding why things are the way they are; looking at examples of how other institutions have addressed challenges and opportunities around representation; and then reaching back into your existing community, while extending your networks, to engage with people who more accurately reflect the audiences you wish to serve and talent you wish to access.”

Read more: 10 of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s all-time best pieces of music >

Julian Lloyd Webber catches up with Isata and Sheku Kanneh-Mason

Rooke adds, crucially: “It is good to consult, but we must not expect Black people to have all the answers.”

“Imagine someone has just been knocked over by a car. You can ask them what happened; you can ask them how it has affected them; and you can even ask them what they think should be done.

“It would be unfair, though, to expect them get off their stretcher; consult the driver and advise the driver on how they might improve their steering to make it to the hospital.”

What tips does Rooke have for young composers eager to follow in his footsteps? “To be a composer is an active thing – one has to compose,” he says. “So plug on and don’t listen to doubts.”

Matthew Rooke’s new orchestral reduction of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, featuring a new translation of the libretto by Janice Galloway, will be performed and recorded by Byre Opera this summer, prior to touring in 2022. Visit www.matthewrooke.co.uk to find out more.