How safe is your instrument? We reveal the science on singing, woodwind and brass so far

12 October 2020, 17:30 | Updated: 12 October 2020, 17:39

Is it safe to sing in a choir, and play wind and brass instruments again? Here’s what we know about the transmission risks involved in making music, as the world still navigates the coronavirus crisis.

It’s been seven months since many musicians around the country have played together, due to the ongoing coronavirus crisis.

Currently in England, indoor concerts can only take place with a socially distanced audience. And it seems unlikely the government will move to ‘Stage Five’ of its five-stage plan – concerts with a full audience – while there is increasing concern around rising numbers in coronavirus cases.

But are there any specific risks involved in music-making? Here’s the most up-to-date science on your instrument.

Read more: What are the new rules for rehearsals, concerts and live music venues? >

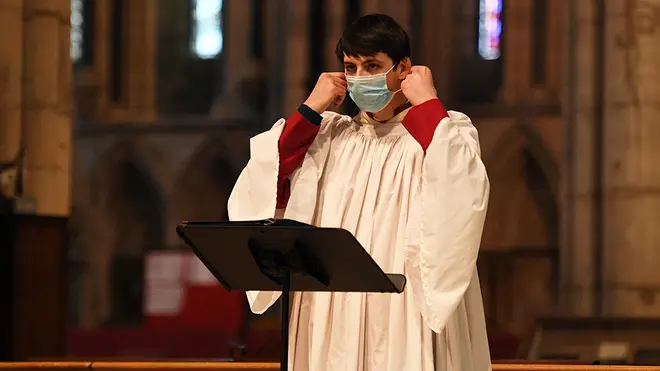

"Increasing evidence" shouting and singing increases coronavirus transmission

How safe is singing?

On 12 October, the government’s deputy chief medical officer Prof Jonathan Van-Tam said scientists “have increasingly strong evidence that shouting and singing [make] the expulsion of virus-laden particles go further and the transmission therefore become more intense” (watch above).

In a government-funded study, also backed by Public Health England, loud singing and speaking were found to emit increased quantities of aerosols – tiny particles of moisture produced through breathing and speaking. In a poorly ventilated space, like a closed rehearsal room, they can remain in the air for several hours.

Since the study, government guidance for singers has included performing at least one metre apart from each other, and singing outdoors where possible. Room ventilation is also encouraged, as well as limiting numbers of performers and socially-distanced audience members, and limiting social gathering opportunities at rehearsals or performances.

Even after scientific testing, it’s worth noting there is still a higher level of risk perceived for singing, above any other form of music-making.

But that’s not to say it can’t happen in a safe, controlled way – as proven by this musical theatre spectacular over the weekend, before which all singers tested negative for coronavirus.

Is it safe to play a wind or brass instrument?

Near the start of the pandemic, health experts feared brass and wind instruments could act as COVID-19 ‘superspreaders’ – not a completely unfounded fear, as choir rehearsals and concerts have been known to spread the disease.

In early May, the musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic took part in an experiment, in which particles emitted from playing wind and brass instruments were ultimately found to be pretty inconsequential.

In fact, merely speaking at a normal volume appeared to cause particles to travel further. It became clear that the particles stayed inside the instruments.

Now in England, similarly to general social gatherings, government advice for woodwind and brass playing includes social distancing between players, as well as room ventilation and wearing masks during break times.

Elsewhere, Brass Band England advises ensembles to use screens to separate rows, where social distancing isn’t possible, and to limit group size. They also encourage more rigorous hygiene, such as emptying water keys into a cloth only touched by the player.

Generally speaking, it’s a good idea – pandemic aside – for wind and brass players to maintain general instrument hygiene. A 2011 study by Marshall & Levy found it extremely likely for woodwind and brass players to re-contaminate themselves, and to contaminate any who might share their instrument, with bacteria and viruses.

Reed instruments were found to carry higher microbial loads, while the flute appeared to be the riskiest instrument in terms of causing a virus to spread, as it caused air in its vicinity to travel the furthest.

Is it safe to play a string, keyboard or percussion instrument?

Earlier on in the pandemic, string, percussion and keyboard players had slightly looser rules than singers or woodwind and brass players, when it came to performing or rehearsing in a group setting.

Now, they abide by the same rules as other instrumentalists – but the risk level is still perceived to be slightly lower due to reduced emission of those “virus-laden particles”.

The government guidance currently includes social distancing, playing outdoors where possible and reducing group sizes.

When will music-making go back to normal?

Nobody quite knows. But the feeling as the pandemic has gone on, is that musicians – particularly freelancers, many of whom feel unsupported during the pandemic – need to be able to make live music again, in a safe and economical way.

Violinist Nicola Benedetti, speaking in a recent interview with Classic FM’s sister station LBC, said the “plight” of freelance artists “is being left out”.

She added: “We want to see private and public sector working together better to implement the creative ideas that are safe and that work, and that we could be putting to use and we see across Europe but just aren’t being implemented.

“We could do a lot better than we’re doing now.”