On Air Now

Calm Classics with Myleene Klass 10pm - 1am

4 October 2023, 15:40 | Updated: 9 October 2023, 17:53

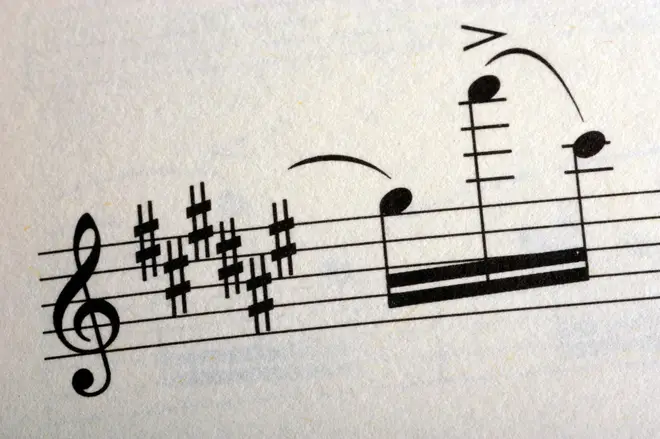

Sharps and flats are most easily described as the black keys on the piano. But what is the difference, and which is which?

Sharp notes and flat notes are the black notes on a standard piano keyboard, and they are at the same time exactly the same, and completely the opposite, of each other.

They are the same, in that every sharp note is the equivalent, or ‘enharmonic equivalent’ to use the full term, to a flat note (and vice versa) in modern Western music. Think of enharmonic equivalents like different spellings of same-sounding words.

But they are also opposites, in that when it comes to Western scales – the set sequences of notes that form the building blocks of classical music – sharps and flats technically don’t coexist: at any given time, the context of a specific scale throws you into a universe that only abides by sharps, or one that only abides by flats (but never by both in one scale).

That’s not to mention the history of Western tuning – and the context of different tuning systems around the world – that before ‘even temperament’ didn’t deem flats and sharps as equivalent to each other at all.

Let’s go on…

Read more: How many keys does a standard piano have? It’s 88 – here’s why...

This piano doesn't have any black keys

A sharp note is a note that’s raised. Going back to the piano keyboard, the notes are arranged in order from the lowest on the furthest left, up to the highest on the furthest right.

So, to the right of the white note A, you would find a black note. This note is called ‘A sharp’, the ‘sharp note’ variation of the original note, and it raises the note by one semitone. After A sharp, if you were to go one note higher again, you would arrive at B.

If we need to differentiate the A from its sharpened version, we call it ‘A natural’.

The interval between a natural note and its ‘sharp note’ – or ‘flat’ note (but we get onto that later) – neighbour is called a ‘semitone’, the smallest conventional interval in traditional Western classical music notation.

So what about ‘flats’, then?

Read more: What’s so creepy about a semitone?

A flat note is a note that’s lowered. Going back to the keyboard, we would call all black notes left of their ‘natural’ white note neighbour a flat note.

Let’s start from A again. The note left of A on the keyboard is ‘A flat’ and it lowers the note by a semitone. After ‘A flat’, if you were to go one note lower, you would arrive at G.

You can collectively refer to sharps and flats as ‘accidentals’, to distinguish them from their natural note neighbours. And you can have double sharps, notated with a small ‘x’ symbol in music notation, or double flats, notated as two of the small ‘b’ symbols, to raise or lower natural notes by a tone (two semitones) instead of just one semitone.

Read more: What is the circle of fifths?

Microtonal piano shown in clip

A sharp raises a note, a flat lowers it.

A sharp is notated with the # symbol (yes, a ‘hashtag’ if you’re below a certain age…). Sharp derives from dièse in French, or diesis from Greek, and means “higher in pitch.”

A flat is notated with the ♭ symbol, which is like a small ‘b’ – literally “soft B” in Italian, which a lot of classical music notation derives from – and means “lower in pitch”.

The sharps and the flats of the standard keyboard today are the same notes as each other, but whether they are a sharp or a flat is to do with context.

Let’s go back to the two examples of the three-note sequences we named above: in A A# B, the pitch moves as the sharp made the starting note one semitone higher. In A, A♭, G, the pitch moves down as the flat made the A one semitone lower.

We could have just as easily gone up in terms of pitch with A, B♭, B (still arriving at B, still with a semitone between each note) and could have just as easily gone down in terms of pitch with A, G#, G (still arriving at G, still with a semitone between each note). They sound just the same as the first examples we gave.

So what would change the context?

Scales.

And equal temperament.

Classic FM Music Teacher of the Year Awards with ABRSM – meet our winners of 2023!

Scales are sequences of notes, tones, and intervals, which move in a specific direction – either up or down – and dividing what is called an octave, in Western classical music.

An octave is the interval of an eighth, which is the distance you go from a note to the pitch and sound frequency that is double that note, making it sound the same to the human ear, but either in a higher (up an octave) or lower (down an octave) version.

Well established scales follow the same rules to split the octave in a predictable way, and these have formed the basis of tonal classical music. Scales can be in the minor or the major key, and they can have either sharps (e.g. C sharp major), or flats (e.g. B flat major), but not both (for example, A flat major doesn’t have any A sharps in it).

You can start these established scales from anywhere on the keyboard, white notes and black, and the sharps or flats of that scale help to give the notes the pitches that build the correct sequence of intervals to create familiar harmonies.

Read more: Why are there only 12 notes in Western music?

Equal temperament is a tuning system that sticks to established intervals when dividing the octave into a scale.

The most common tuning system since the 18th century has been 12-tone equal temperament. In this system, flats sound equivalent to sharps, for example the note below G is known as both G flat, or F sharp.

These notes are enharmonic equivalents (different spellings of same-sounding words).

Around 500 years ago, G flat and F sharp wouldn’t only have looked different, been “spelt” differently, but also sounded different too. There were very slight pitch variations between flats and their now-equivalent sharps (and vice versa).

Read more: How did music notation actually begin?

Introducing the Baroque Trumpet with Alison Balsom | Classic FM

While we’re on the topic of slight pitch variations, let’s step away from the music theory side of sharps and flats, and think about them acoustically for a minute.

The definition of a sharp being a note that’s raised, and a flat being one that’s lowered, applies to tuning a single note, a single tone, as well. When an orchestra tunes to a single tone, usually an ‘A’ in Western orchestras, musicians aim to get their note to exactly the same frequency, or pitch, so there is no discord between the notes in the audiences’ ear.

An individual musician’s pitch may be ‘off’ in terms of it being higher – or sharp – and they must tune down and make the note flatter to match the correct pitch. Or their ‘off’ note could be flat, lower than the rest of the orchestra, so they will have to tune it upwards, or become sharper.