On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

21 June 2023, 17:44 | Updated: 22 June 2023, 10:50

75 years after the Empire Windrush docked in Essex, we celebrate the lasting musical legacy of the Windrush generation, and some of its key musical figures.

On 22 June 1948, the Empire Windrush ship arrived at Tilbury docks in Essex.

It carried more than 800 passengers from the Caribbean who had been invited to the UK to help rebuild Britain, filling a labour shortage left by the Second World War.

With them, they brought over jazz, blues, calypso, and a host of other musical styles that enriched and transformed the British music scene.

Read more: 19 Black musicians who have shaped the classical music world

The ‘Windrush generation’ includes anyone who immigrated to Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1971, named after the arrival of one of the most famous ships: the Empire Windrush.

The Windrush brought passengers from Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, among them civil servants, legal and military officials, as well as musicians, artists, and domestic workers.

The British Nationality Act 1948 was making its way through parliament at the time, which granted equal citizenship (at least on paper) to all British nationals as well as those of British colonies.

Many of the Windrush’s passengers answered an advert to sail to Britain at a reduced price, after the Second World War. It is estimated that around half a million people took up this opportunity to relocate to the ‘mother country’.

They were promised jobs in the newly created National Health Service (NHS) and National Rail, military positions, or work in the production industries for steel, coal, iron, and food.

However, when they arrived in the UK they were also met with hostility, intolerance and racism from much of the white population.

In many cases they were blocked from gaining employment in the private sector or from living in private accommodation, and were also barred from many public venues including pubs, clubs, restaurants and churches.

Read more: Hazel Scott, the forgotten jazz star who fought racial segregation

Baroness Floella Benjamin DBE, who came to Britain from Trinidad as a 10 year old in 1960, joined activist Patrick Vernon in campaigning for Windrush Day to be celebrated in the UK – a motion that was eventually granted in 2018.

In a story for BlackHistoryMonth.org, Baroness Benjamin described how she had suggested a ‘Windrush Day’ in Parliament, only to be told that “it wasn’t needed, because we have a Black History Month”.

“That’s missing the point,” she said. “The arrival of the ship in Tilbury in 1948 is a focal point of great magnitude for the Caribbean diaspora. For those who had to overcome so much adversity, it has great significance.”

Listen to ‘Floella’s story: How Windrush hurt a generation’ on Global Player >

The voyage to the UK and the ensuing years were a hurtful experience for many Caribbeans. Uprooted in search of a new future, they left behind a life of familiarity to rebuild a country they hoped to call home, and often lost more than they gained.

On her first-hand experience, Benjamin writes: “Many of my childhood experiences in that new culture and unbelievably hostile environment, were character building. They gave me the tools and fortitude to become the person I am today.”

Read more: 10 Black composers who changed the course of classical music history

The arrival of the Empire Windrush had an immense impact on British music, which can still be seen in the music of today.

Music in the Caribbean was already fused with Latin American, African and Asian influences. So when Caribbean artists and music-lovers arrived, they brought an explosion of jazz, reggae and ska, blues, gospel, Latin and Calypso onto the scene, at a time when London was all about swing and dance bands.

Over time, musical styles fused together. Sound system culture played a large part in Caribbean migrants’ new lives, as they formed their own underground nights and venues having been shut out of the mainstream.

Punk rock and new wave music emerged from genres such as dub, ska, and reggae, and the mid- to late-1970s saw a ska revival in bands including The Specials and Madness.

As music technology developed in leaps and bounds, electronic music genres emerged including dubstep, jungle, garage, grime, and drum and bass.

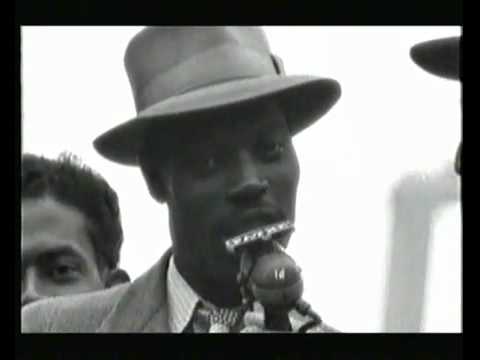

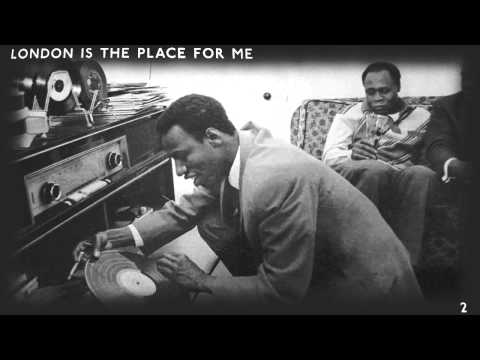

Lord Kitchener - London Is Good Place For Me (Itw, Live Acapella)

Amid the thousands who sailed from the Caribbean to Britain came exciting new musicians, many of whom were already established in their home countries.

Mona Baptiste, a young Trinidadian singer, saxophonist and actress, came to Britain aboard the Empire Windrush and became an international star.

“Mona Baptiste is hardly a footnote in British musical history but in Germany and other parts of western Europe she is still well known despite the fact she died 25 years ago,” said historian David Horsley in a talk in 2018.

“But it was London’s thriving black music scene in the years after the war that really set her on the road to success and saw her performing with some of the biggest names in show business.”

Baptiste was born to a prominent family in her hometown, travelling in first class on her way to the UK.

“Mona breaks stereotypes,” author Benjamin Zephaniah told The Bookseller in 2022, on writing a children’s book about Baptiste.

“She’s not one of the men, either the ex-military men who fought for Britain, or one of the people in the Caribbean who thought, ‘I’m going to help rebuild the mother country’. She’s not thinking about coming and working on the trains, on the buses or in the factories. She wants to be a star.”

And a star she became, recording music in English, French and German, including a version of Nat King Cole’s ‘Calypso Blues’. After settling in Germany she also began to make film appearances, including starring in the titular soprano role of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess for East German television.

Mona Baptiste - Calypso Blues

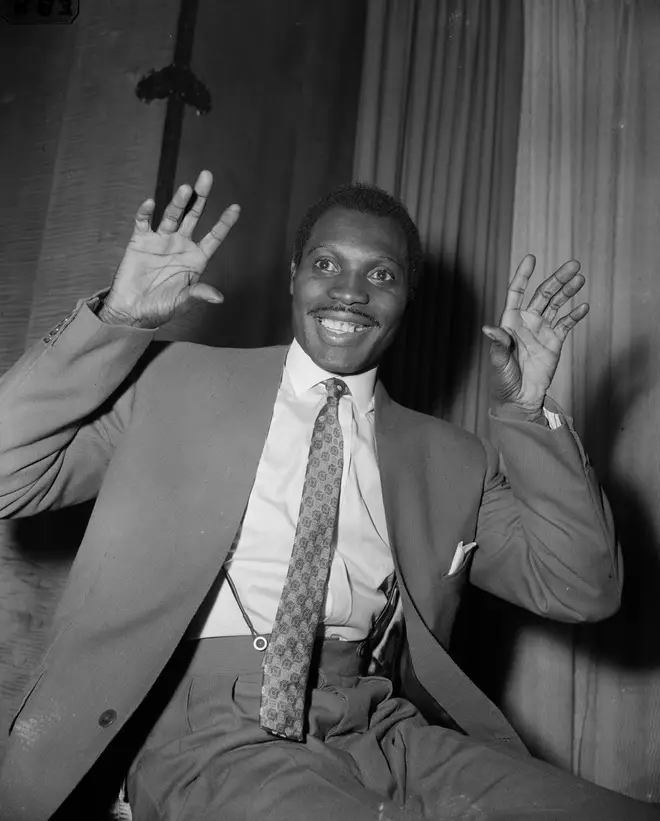

There was also the arrival of the Calypsonians. Lord Beginner, an already-celebrated Trinidadian singer, immigrated to England in 1948 along with Lord Kitchener and Lord Woodbine, having toured Jamaica together the previous year.

On arriving in Britain, Beginner embarked on a music career playing in clubs throughout London, and Kitchener became known as the ‘Calypso King’, after singing his now-famous hit ‘London is the Place for Me’ to the awaiting press as he stepped onto dry land from the Empire Windrush.

Kitchener, whose real name was Aldwyn Roberts, became an icon to those first 5,000 Caribbean migrants. His music spoke of home and a life many longed for, but could not return to.

Artists like Beginner and Kitchener exploded onto the British music scene, and helped Calypso achieve international success in the 1950s.

The year Britain began celebrating Windrush Day, 2018, was also the year the Windrush Scandal erupted. It emerged that British citizens who had arrived as children during the Windrush generation were being wrongly detained, denied healthcare, or threatened with deportation.

Reports of mistreatment of Caribbean-born Brits began to surface around 2013, but the scandal didn’t erupt into public awareness for another five years, in 2018.

Alarming revelations were made that more than 160 people were wrongly detained. At least 83 of those had been wrongly deported, 11 of whom had since died.

Then-prime minister Theresa May apologised at the time, and an independent inquiry released in 2020 made 30 recommendations, all of which were accepted by then-home secretary Priti Patel. In 2019, a Windrush Compensation Scheme was also established.

However, at the beginning of 2023, current home secretary Suella Braverman dropped three of those commitments.

Human Rights Watch also accused the compensation scheme of failing the community, who felt it was “designed to fail the people who were supposed to benefit from it”, after only 25 percent of claimants had received any compensation as of June 2022.

The Guardian also revealed that, in the same month of the 75th anniversary of the Windrush’s arrival, the Home Office has ‘quietly disbanded’ the unit responsible for preventing a repeat of history within the department.

Britain wouldn’t be the place it is today without the extraordinary contribution of the Windrush generation. Parents left behind children, and thousands abandoned a life of familiarity, to find work and a new life.

They transformed communities with their music, food and culture – and in return, deserved recognition and a safe place to call home. But many of them didn’t get that.

In 2020, King Charles, then Prince of Wales, paid tribute to the “immeasurable difference” the generation of immigrants, their children and their grandchildren have made “to so many aspects of our public life, to our culture and to every sector of our economy”.