Why musicians have all the skills to be the best spies

1 October 2021, 15:59 | Updated: 1 October 2021, 16:02

What do World War II codebreakers at Bletchley Park, a British opera star, and a Renaissance composer have in common? We explore the intertwined history of music and espionage.

During World War II, potential codebreakers arriving for interview at Bletchley Park were asked if they could read music.

Why? Staff at the British codebreaking HQ were on the lookout for musicians, after they found there to be a strong correlation between musicians and the ability to solve puzzles.

There are reports that there were so many musicians at Bletchley, that they formed an orchestra!

The link between musical ability and mathematical prowess, while highly debated, can be traced back to the time of Plato.

Read More: Music really does make students smarter, and this study proves it

When playing a musical instrument, for instance, musicians constantly have to think about where their hands, or voices will move next, how to adjust for new tempos, and translating accidentals and key signatures on sight.

The same expertise is needed for cryptography – the art of solving codes. Patience and perseverance are often cited as two of the vital skills codebreakers need, the same skills used by musicians during their hours of practice.

Reading a score is also an important skill because it involves studying the following; the pieces structure, its instrumentation, and recognising the patterns which make up a musical idea.

When it comes to cryptography, understanding the structure of the code is key, otherwise breaking it becomes near impossible.

Read more: What is the Fibonacci Sequence – and why is it the secret to musical greatness?

A history of musical spies

The codebreakers at Bletchley aren't the only example of musicians being involved in espionage.

There are many stories surrounding court musicians in the 16th and 17th centuries who were often recruited by the secret service due to their access to the private chambers of important figures.

Musicians such as John Dowland, Thomas Morley and Alfonso Ferrabosco all conducted espionage, but one of the earliest examples of a musical spy comes in the form of Renaissance composer Pierre Alamire.

Under the guise of a merchant of manuscripts, chaplain, singer and instrumentalist Alamire travelled across Europe as a spy for King Henry VIII.

However, it was later found out that Alamire was a double agent, and had been spying for Richard de la Pole, the pretender to the English throne. He wisely never returned to England after this was uncovered.

Dowland’s 'Lacrimae Coactae', performed with new lyrics at Wigmore Hall

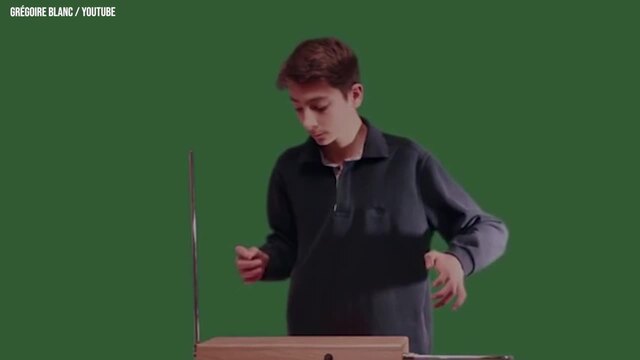

More modern day examples of musical spies include Leon Theremin, the inventor of the instrument of the same.

When the inventor took his newly discovered instrument on tour across the world, he was also collecting information which he could take back to his homeland, Russia.

Theremin's espionage continued for the 11 years he lived in New York, before the outbreak of the Second World War.

When he did choose to flee the country fearing for his own safety, he left without even telling his wife, which led to wild theories that he had in fact been kidnapped by Soviet agents.

Debussy’s ‘Clair de lune’, played on a THEREMIN

British opera star, Margery Booth, became a British spy after her marriage to a German man took her to Germany in 1935.

Information she provided as a spy was used to convict two Nazi propaganda broadcasters, both of whom were hanged for treason.

It's alleged she even once sung for Hitler, whilst concealing secret documents in her dress which a British Officer had just passed onto her.

Read more: Did you know Hitler once wrote an opera?

Booth was captured in 1944 as a suspected spy by the Gestapo. Despite being tortured, she never gave up any information, and on release, she was liberated in Germany by the US army.

While we don't yet know the identity of the next James Bond, maybe the casting directors should be looking to the local conservatoire for their next super spy.