On Air Now

Calm Classics with Myleene Klass 10pm - 1am

21 May 2021, 14:28 | Updated: 21 May 2021, 16:55

The story of a barrier-breaking African American composer and musician who had a deep friendship – and for a while shared a roof – with the pioneering classical great, Florence Price.

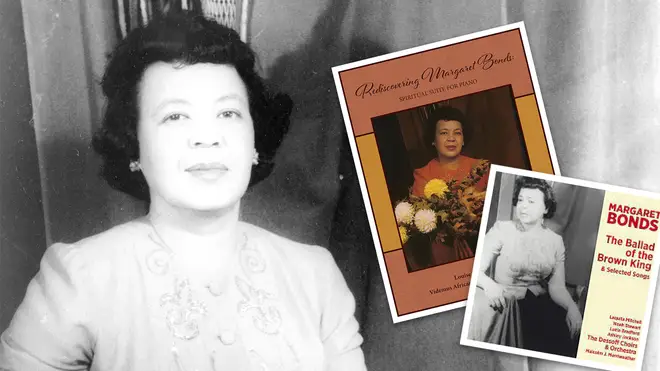

Margaret Bonds was one of 20th-century America’s great music-makers, who forged a path as a Black woman composer in 1930s Chicago.

Born Margaret Jeanette Allison Majors, Bonds came into the world on 3 March 1913 in Chicago, Illinois.

Her mother, Estella Bonds, was a musician, piano teacher and the local church’s choral director and organist. She taught piano to young Margaret from a very early age.

Her father, Monroe Majors, was a physician and lecturer. But her parents had an unhappy marriage, and when they split, Margaret’s last name was changed to Bonds.

Margaret spent most of her childhood with her mother, whose household was often a guesthouse for leading African American literary and artistic figures from the Chicago area.

Aged eight, this young prodigy had won a scholarship to the Coleridge-Taylor Music School (more on Samuel Coleridge-Taylor just here).

Read more: 9 Black composers who changed the course of classical music

During high school, Margaret Bonds studied composition and piano with Florence Price – the first African American woman to be recognised as a symphonic composer and to have her work performed by major orchestras.

Price’s writing, as Bonds’ later would, married the European classical tradition with melodies from African American spirituals and folk tunes she grew up with.

Read more: The inspirational life of Florence Price, and why her story matters today

By the age of 16, Bonds was studying at Northwestern University for a Bachelor of Music and later, a Masters in piano and composition. But she was in a minority of Black students, and the environment was racist, intimidating and almost intolerable.

Bonds recalls in an interview with James Hatch: “I was in this prejudiced university, this terribly prejudiced place – I was looking in the basement of the Evanston Public Library where they had the poetry. I came in contact with this wonderful poem, ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’, and I’m sure it helped my feelings of security.

“Because in that poem he [Langston Hughes] tells how great the Black man is: And if I had any misgivings, which I would have to have – here you are in a setup where the restaurants won’t serve you and you’re going to college, you’re sacrificing, trying to get through school – and I know that poem helped save me.”

Chineke! Orchestra plays Florence Price Symphony No. 1 in E minor

Langston Hughes was a leading poet and figure of the Harlem Renaissance, in whom Bonds found a life-long friend and collaborator.

Soon after they first met, Bonds set one of his best-known poems, ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’, to music.

During the Civil Rights Movement, Bonds and Hughes worked on music celebrating African American culture and values. Bonds would compose two important works dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr, one of them the Ballad of the Brown King, which was one of the duo’s most frequently performed pieces.

When Langston Hughes died in 1967, Bonds retreated. She left her husband and daughter in New York, and moved to Los Angeles where she remained until her death in 1972.

Bonds sought to bring her own elegant style to African American music, and to blend the sounds of spirituals and songs with the structure of Western classical tradition.

She is best remembered for her popular arrangements of African American spirituals including ‘Troubled Water’ (watch below) and ‘Three Dream Portraits’, a work for voice and piano set to Hughes’ poetry.

Probably Bonds’ best-known setting is ‘He’s Got the Whole World in His Hand’, which she arranged for soprano Leontyne Price in 1963.

Read more: 11 Black opera singers you should know about

Troubled Water by Margaret Bonds (Samantha Ege, piano)

Price and Bonds had a great deal in common, both being African American, classically trained composers who married African-American sounds with Western structures.

In 1932, Price and Bonds both scooped a prestigious Wanamaker award – Price for her Symphony in E minor, Bonds for a song. And in 1934, when Price’s Piano Concerto in D Minor would be performed by the Woman’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago, Price made sure Bonds would be the pianist on the day, leading to further musical opportunities for her friend.

That same year, sure enough Bonds became the first African American to perform with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Bonds and Price even lived together for a brief while, when the elder was teaching the younger. Price went through a divorce and needed a place to stay, so Bonds and her mother took her in for a while.

In a time where Black female musicians’ voices were often silenced, Price and Bonds’ mutual support helped them break down barriers and make their important musical offerings heard.

Hear Dorothy Rudd Moore’s music played on Chi-chi’s Classical Champions on Classic FM from 23 May onwards.