On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

19 December 2022, 17:19 | Updated: 19 December 2022, 17:22

On the 25th anniversary of the release of James Cameron’s ‘Titanic’ (1997), we explore the story of the miracle violin that holds a lifetime of stories in the grain of its wood.

Of all the instruments in the world, violins and other string instruments are often renowned for their longevity, with the centuries-old creations of Italian luthiers, Amati and Stradivari, holding hundreds of years’ worth of stories, and selling for millions of pounds today.

Few, however, can compete with that of the Titanic violin – the instrument played in April 1912, as the RMS Titanic sank into the North Atlantic Ocean after its fatal collision with an iceberg.

Today, the violin is held at the Titanic Museum in Tennessee, as part of their public display of artefacts and memorabilia from the ship.

But the story of how it got there is not quite so simple...

Read more: The Holocaust-surviving violins that endured atrocities to tell a vital story

RMS Titanic seen in old news report

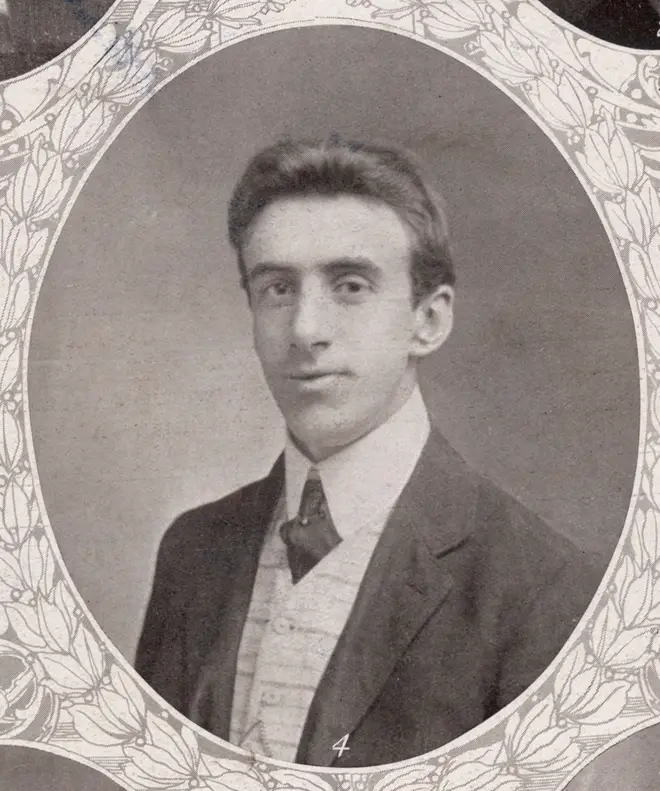

The now-famous violin was crafted in Germany in 1910, and was gifted to Wallace Hartley of Colne, Lancashire, as an engagement present from his new fiancée Maria Robinson. An inscription on the instrument’s tailpiece read, ‘For Wallace, on the occasion of our engagement, from Maria’.

The sweethearts likely met in Leeds, where Hartley played as a musician in various institutions around the city. Having previously provided musical entertainment on the RMS Mauretania, Hartley was contacted shortly before the RMS Titanic departed from Southampton on its maiden voyage with a request that he become its bandleader.

After his initial reluctance at leaving his fiancée, Hartley agreed to join the transatlantic crossing, hoping to secure future work with some new contacts before returning for his June wedding.

Tragically, the wedding never took place. Four days into the crossing, the Titanic hit an iceberg in the North Atlantic ocean, and sank on the 15 April 1912, taking more than 1,500 passengers and crew members with it – Hartley included.

Read more: Great explorer immortalised as his old floorboards are made into a unique violin

In a depiction made famous by the 1997 film Titanic (see above), the eight musicians on board the ship continued to play amid the havoc, as women, children and first-class passengers were loaded hurriedly onto lifeboats.

At maximum capacity, the lifeboats barely had space for half the people on the ship, and as the wooden boats began to depart with seats still vacant, it soon became clear that many of those still on board the rapidly sinking cruise liner would not be saved.

As was his command, bandleader Wallace H. Hartley gathered his seven fellow musicians to play music in an attempt to calm the pandemonium and still people’s fears. Survivors of the ship report that the band played upbeat music, including ragtime and popular comic songs of the late 19th and early 20th century.

One of the popular myths surrounding the Titanic and its historic fate is that the band played the hymn ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ in their final moments. Some accounts dispute this, claiming that the musicians were last heard playing Archibald Joyce’s waltz, ‘Dream of Autumn’, before abandoning their instruments.

Read more: How a leading symphony orchestra narrowly avoided playing on the Titanic the night it sank

If the musicians were indeed playing music to the very end, it does seem likely that Hartley would have chosen the hymn as their swan song.

Hartley’s father, Albion, was the choirmaster at the Methodist chapel in the family’s hometown, and had introduced ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ to the congregation.

Hartley had also told a former colleague on the Mauretania that, should he ever find himself aboard a sinking ship, the hymn would be one of two pieces he would play in his final moments – a chilling foreshadowing of events to come.

Only three of the musicians’ bodies were recovered from the wreckage, including Hartley’s. A detailed inventory documents the personal effects that were found with him, including a gold fountain pen and silver match box, both engraved with his initials, and a diamond solitaire ring.

Despite some reports to the contrary, there is no evidence that his violin was found strapped to his chest in its case. We do know, however, that it must have been recovered, along with a satchel embossed with Hartley’s initials, as a telegram transcript from Maria Robinson to the Provincial Secretary of Nova Scotia reads, ‘I would be most grateful if you could convey my heartfelt thanks to all who have made possible the return of my late fiancé’s violin’.

When Robinson died in 1939, her sister gave the violin to the Bridlington Salvation Army, who passed it on to a violin teacher. The teacher passed it on further, and in 2004 it was rediscovered in an attic in the UK.

Sceptics initially refused to believe that this could be the real thing, assuming that the violin would have been so badly damaged by water that it simply could not have survived.

However, after nine years of evidence gathering and forensic analysis, including CT scans and a certification by the Gemological Association of Great Britain, it was confirmed that this was, in fact, the violin that Wallace Hartley had played aboard the RMS Titanic.

Forensic experts certified that the engraving on the metal tailpiece was “contemporary with those made in 1910”, and that the instrument’s “corrosion deposits were considered compatible with immersion in sea water”.

On 19 October 2013, the violin was sold at auction by Henry Aldridge & Son in Wiltshire for £900,000 (equivalent to over £1,000,000 in 2022), a record figure for Titanic memorabilia. The previous record was thought to have been £220,000 paid in 2011 for a plan of the ship that had been used to inform the inquiry into the ship’s sinking.

The violin is irreparably damaged and deemed unplayable, with two large cracks caused by water damage and only two remaining strings. Its current owners are unknown, but believed to be British.

As for Hartley, he was buried in his hometown of Colne in Lancashire, at a funeral service that was attended by over 20,000 people, and included the hymn that will forever be associated with him, ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’.

The headstone of his final resting place includes an inscription of the hymn’s opening notes, above a violin carved out of stone.