On Air Now

Early Breakfast with Lucy Coward 4am - 6:30am

17 August 2017, 17:03 | Updated: 23 February 2018, 12:38

It’s 60 years since Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story was premiered in Washington in 1957. But was it a musical or an opera? Here's why Bernstein’s award-winning work bridged the gap between musicals and opera...

Immensely challenging to sing and perform, West Side Story is hugely popular with musical theatre fans and opera-lovers alike, but why?

Many people believe West Side Story is the pinnacle of musical theatre achievement, thanks to the way it blurred the lines between musical and opera. Coupled with Bernstein’s miraculous tunes, here's how the genius composer managed to bridge the gap between musical theatre and opera:

“You just know” - Leonard Bernstein

OK, admittedly this isn’t the strongest point to start on, but bear with us...

In 1954, Bernstein became the first conductor to present a series of television lectures on Classical music and during a particular programme about the history of American musical theatre, he was asked: “When is a particular work an operetta, and when is it an opera?”

Using South Pacific as an example, Bernstein explained that when Emile sings ‘Some Enchanted Evening’ it is a musical, but when Bloody Mary sings ‘Bali Ha'i’ we are listening to opera.

“You just know,” he said. He went on to explain that the fundamental features are the sound, the tone, and most importantly the nature of the story.

How does this concept apply to West Side Story?

Using Bernstein's analysis, you can firstly easily divide songs like ‘Maria’ or ‘Somewhere’ into the opera category, meanwhile, ‘America’ and ‘Gee, Officer Krupke’ most certainly belong in the musical world.

Secondly, the lyrics written by Stephen Sondheim can also be split into serious/opera and humorous/musical.

And finally, with regards to the nature of the story, West Side Story is deadly serious. Unlike other musicals of the time, the work focuses on dark themes and features very little comedy, not to mention *SPOILER ALERT* it ends on a tragic note with the death of one of the leads. It also draws heavily from themes in Romeo and Juliet: there are two rival gangs on the streets of New York, two families at war, two lovers, one drawn from each family.

So like South Pacific, West Side Story can be considered an opera in parts, and musical theatre in others. But does the composer’s analysis have any bearing on how we perceive the work?

Richard Rodgers, the composer of South Pacific, wrote over 40 musicals throughout his career, all of which featured on Broadway. He is, without a doubt, a composer of musical theatre.

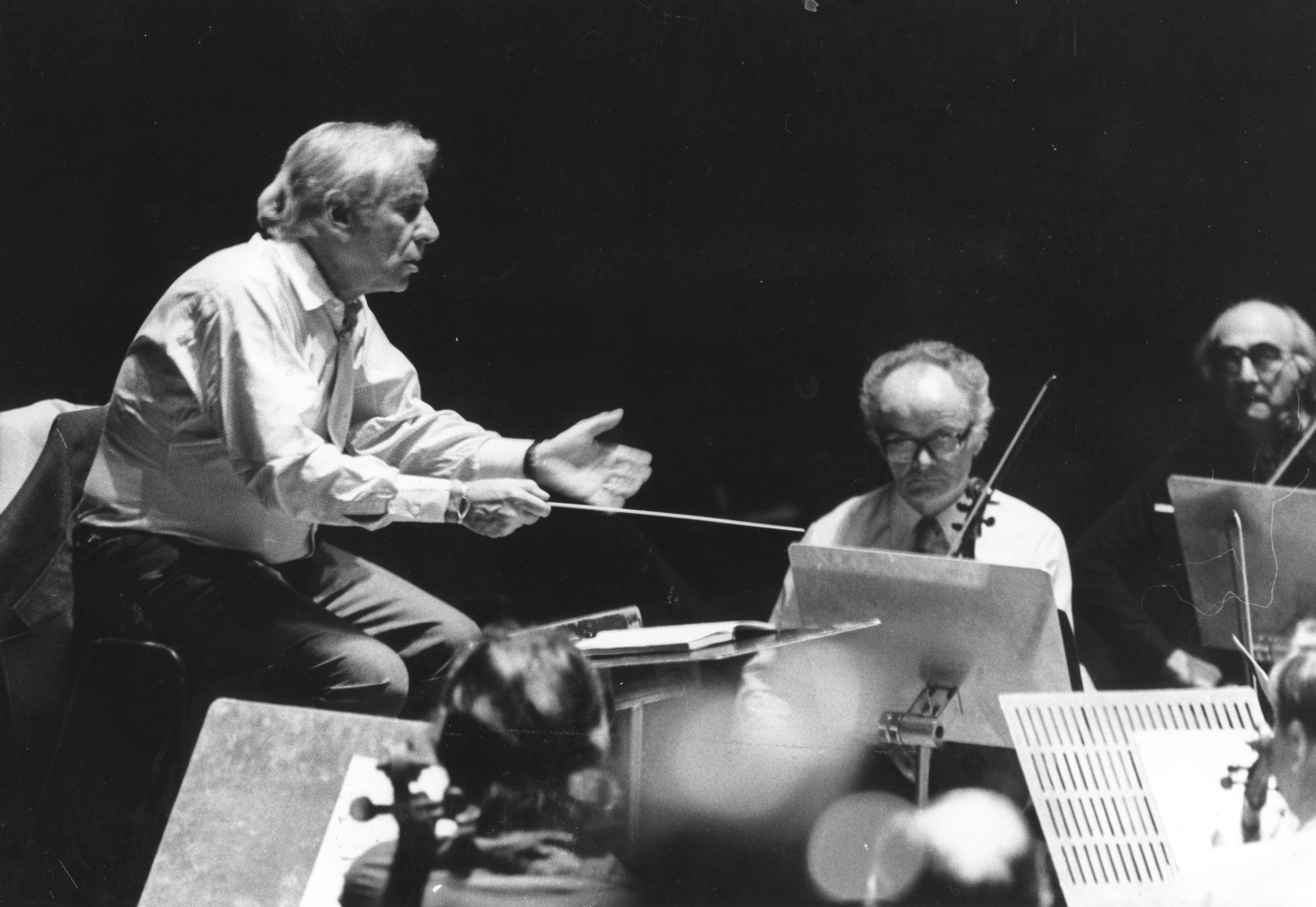

Bernstein, on the other hand, is a whole different ballgame. After becoming an overnight conducting sensation, he began to compose and there was hardly a genre he did not explore – ballet, opera, musicals, symphonies, choral, chamber music. He is undoubtedly a classical composer.

Bernstein was not the only composer whose work falls into both the classical music/musical theatre abyss

Porgy and Bess, nowadays considered to be an ‘American folk opera’, was composed by fellow New-York based composer George Gershwin in 1935. However, after premiering in Boston before moving to Broadway, it was not until 1976 that it was performed at an opera house.

Do we need to categorise the work?

Bernstein was a composer who experimented, crossed boundaries and wasn’t afraid to let his hair down - that’s why we’ve got an extensive list of all the reasons we love him.

Yes, the catchy rhythms of ‘America’ from West Side Story are not considered to be classical music in the traditional sense, but even our very own John Suchet would argue that ‘Maria’ is an aria, and traditionalist or not, we all can agree the arias belong in the world of opera.

West Side Story may fit into the musical category, the opera category, or could be considered to be in a league of its own. Whether or not it needs to be shunted into one singular category, it effectively marks a significant turning point in the history of musical theatre.

*dances off into the distance*