Howard Goodall On Beethoven

He has towered over classical music’s landscape for 200 years. His influence, his genius, his challenge hung heavily on the shoulders of all who followed him. When, in 1956, the great guitarist and lyricist Chuck Berry heralded the dawn of the rock ’n’ roll age with a declaration of intent to start music afresh, the shorthand he employed was instantly recognised the world over: “Roll over, Beethoven!”

It was a bold claim and one that proved futile: he chose the one classical composer who wasn’t going to roll over, then, now or ever. Beethoven’s probably out-selling Berry’s back-catalogue right now.

Berry’s choice, though, was proof of Beethoven’s status and a mark of some respect. Indeed, most rock musicians I know have more time for the Viennese colossus than most other classical composers – I suspect they identify as much with his slightly demented, devil-may-care, “it’s the music, stupid” attitude as much as with the pounding, uncompromising grandeur of his compositions.

I have a confession to make, however. In spite of Fidelio, the Ninth Symphony, the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, the final quartets and the Missa Solemnis, all of which are sublime masterpieces, I cannot call myself a Ludwig van fan. The weakness is mine, not his, I realise.

But since people have often asked me about this quirk in my listening preferences I have had to think quite hard about what it is that bothers me about the bulk of Beethoven’s work. It is not as if I haven’t been exposed to the full extent of his work as part of my musical education; I have. Nor have I picked up this antipathy from some eccentric teacher at an impressionable age – all my teachers revered him, as far as I remember. For me, it’s to do with the difference between the invisible and the visible hand of the creative artist, the dividing line that lies between emotional authenticity and indulgence.

When I peruse a score by or listen to a performance of Bach, Handel or Mozart, I cannot escape the fact that their art is, apparently, mysterious. On the page it looks simple, one could go so far as saying it looks unsophisticated. So how does it sound so beautiful with such economy? With so seemingly slender a range of resources?

Bach is the most elusive of all: a small number of instruments with the barest minimum of information added to the notes on the page; no guidance as to who exactly plays what, how to voice the chords (often indicated by a few squiggly numbers known as ‘figured bass’ – musicians’ shorthand); nothing about dynamics (volume and the map of its rise and fall), tempo (speed), accent (emphasis) or phrasing (melody shape).

It is like reading a book without punctuation or flying a small plane without instruments. And yet what happens when it reads off the page is truly miraculous. It is transformed into a sound of incomparable grace, harmony and depth from these tiniest of instructions. To me, this is what makes music the most mystical and extraordinary of all the arts and what leads some to conclude that some kind of divinity is at work in its creation. Only God, they say, can pull off a trick as awesome as this – wine from water, if you like.

I agree with Mendelssohn’s estimation of Bach’s St Matthew Passion as something so great as to defy analysis.

When I examine a Beethoven score, by contrast, I feel quite strongly the presence of the composer in every nuance, every detailed instruction, every decision he makes. His brilliance is everywhere to be seen and admired: his deft manipulation of musical architecture; his deliberate pushing of the boundaries of what his instruments and his players could do; his mastery of the growing scale and potential of the symphony orchestra. It’s all there in its virtuoso glory.

But there’s the rub. I feel I am being ‘impressed’ by Beethoven’s genius rather than being allowed to uncover its secrets for myself. It is the difference, in my estimation, between the kind of actor who so completely becomes the part they are playing that you forget or cannot detect what they are doing as actors, technically, to achieve it, and the kind of actor who seems to be enjoying being an actor as much as being another person – you are aware of the skill, purpose or dexterity of the performer themselves.

This for me is a stumbling block. Beethoven’s skill appears to me to be the first thing I experience in his music, even if I know beyond the initial impression there is much to enjoy. It is as if he is saying, “Look at me, folks, I can do this and this and this, I am a wizard of the keys.” Real wizards, surely, don’t need to tell anyone they can do spells. They just do them.

Four reasons to like Beethoven even if he’s not your No.1...

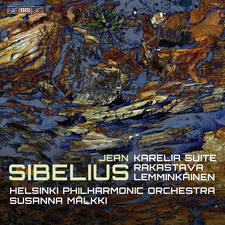

• He inspired every other composer of the 19th century. Without Ludwig, there would be no Mahler, Elgar, Sibelius or Brahms symphonies – he was the trail-blazer they all tried to emulate.

• Elgar’s ‘Nimrod’ from the ‘Enigma’ Variations, a work beloved of Classic FM listeners, is a heart-breaking tribute to Beethoven’s slow movements – no Beethoven, no ‘Nimrod’.

• Although he only wrote one opera (Fidelio, 1814), he showed opera composers like Verdi and Wagner how apparently abstract music could portray drama, even without a text

• In Beethoven’s hands the piano went from gently tinkling “harpsichord plus” to a mighty powerhouse of the modern instrument thanks to the demands he made of it.