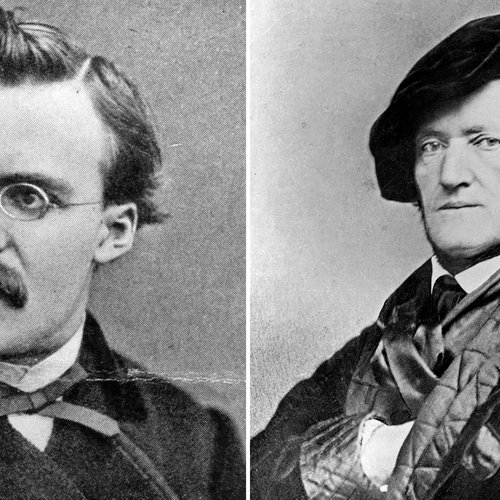

Richard Wagner: A Life

Despite the controversy over his private life, personal convictions and music, it cannot be denied that Richard Wagner changed the face of opera forever.

Wagner is the most hotly debated of all the great composers. For some listeners, his operatic epic The Ring – three operas and a vorspiel (prelude), sustained by a web of leitmotifs (a musical idea representing a person or an object) – represents the pinnacle of Western music. For Mahler there was only “he [Beethoven] and Richard [Wagner] – otherwise nothing”, and WH Auden considered him “the greatest genius of all time”. Others find more sympathy with conductor Thomas Beecham, who during preparations for a performance of Götterdämmerung (Twilight Of The Gods) despaired: “We’ve been rehearsing for two hours and we’re still playing the same bloody tune!”

Few would contest that Wagner’s trailblazing operatic works were the product of a visionary genius. From the super-heated climaxes that crown Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold) and the first act of Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), to Lohengrin’s magical multiple-string textures and the chromatically intensified sensuality of Tristan und Isolde, the influence of Wagner’s music was more far-reaching even than Beethoven’s. A whole school of French composers – Chausson, Duparc and Dukas among them – sprang up, whose music was composed almost in homage to him. The virtuoso orchestral scores of Scriabin, Strauss and Respighi would also have been unthinkable without Wagner’s example. However, for some Rossini’s put-down – “Wagner has good moments, but bad quarters-of-an-hour” – rings true.

Yet whatever the controversy surrounding Wagner’s music, it pales almost into insignificance by comparison with the man and his strongly held views. His serial adultery may seem like small beer now, but at the time the public parading of his latest conquests resulted in his making hasty departures. His self-belief carried him through a number of personal (and financial) crises, although it hardly made him the easiest of people to get along with.

Even more contentious were his writings, in which he pontificated on a series of topics, ranging from vegetarianism and hygiene to vivisection and Buddhism. His extreme nationalism, support of Bismarck, and anti-Semitism – laid bare in Das Judenthum in der Musik (‘udaism in Music) – were embraced by the Nazis, for whom Wagner’s music became a symbol of German supremacy.

Such unfortunate political associations aside, Wagner’s impact on the operatic world was incalculable. He took orchestral writing from the rum-tee-tum accompaniments of popular Italian opera to a cutting-edge virtuosity to match anything in the concert hall. Singers were no longer called upon to deliver stratospheric set-piece arias, but to sing more heroically for unprecedented lengths of time, often requiring great stamina.

For Wagner, opera was not just about the voices but a Gesamtkunstwerk (complete art-work) combining music, drama, scenery, costumes and stagecraft in one unified whole. Nothing was left to chance, with even the fall of the curtain at the end of each act timed to maximum effect. The world of opera would never be the same.

Yet for all his colossal impact on cultural life during his later years, Wagner’s beginnings were far from auspicious. He was considered the least musical child in his large family and following a decidedly bumpy ride through his general education was left to teach himself to play the piano. His studentship was punctuated by bouts of truancy, drunkenness and gambling, and it not was until 1831 (when he was 18) that he buckled down and got to grips with some of music’s technical fundamentals under the watchful eye of Theodor Weinlig, a gifted Leipzig church musician.

Falling under the influence of “Young Germany” – the hippies of the 1830s, dedicated to free love – Wagner produced his first two completed operas, Die Feen (The Fairies, 1833) and Das Liebesverbot (The Ban On Love’, 1834), which found him struggling to break free of the influences of Weber, Marschner and Spontini. Shortly after he embarked on a disastrous marriage to the actress Minna Planer, who ran off with an army officer but was forced to come back to Wagner after the former quickly tired of her attentions.

Money, as for much of Wagner’s life, was in short supply, and during a protracted stay in Paris (1839-42) he was forced to take on menial tasks just to keep the wolves from the door. Artistically he had turned the corner and having moved to Dresden, he scored hits with Rienzi (premiered 1842) and Die Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman, 1843).

Never one to stand still artistically, Wagner attempted in his next opera Tannhäuser (1845) to raise the bar in terms of its expressive range and epic structure. It all proved too much for the orchestra, singers and audience, but despite the work’s initial failure Wagner was slowly winning a band of devoted followers. Not the least of these was Liszt, who conducted the successful premiere of Lohengrin in 1850 in the wake of Wagner’s revolutionary involvement during the 1848 uprisings, which resulted in his fleeing first to Weimar and then Zurich.

At first everything seemed relatively peaceful in the Wagner household. Living in Swiss exile, Wagner began focusing his attention on the libretto for his Ring cycle. Yet once again his constant need for adoring female companions led him to fall in love again, this time with Jessie Laussot, the unhappily married daughter of a Bordeaux patron. They were on the point of eloping when Jessie got cold feet and informed her husband and father of the situation.

The already strained relations between Wagner and Minna reached the point of no return when he became involved with Mathilde Wesendonck, another married woman whose husband was a supporter of the composer’s. His emotions surging, Wagner broke off work on The Ring mid-stream and began sketches for his erotically charged masterwork, Tristan und Isolde. Ultimately he was forced to flee once again, this time on his own and to Venice.

Following several years of travelling around Europe, with little to show for it except for Tristan and early work on Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Wagner once again found himself on his beam end. Just as it seemed he might flounder altogether, a helping hand emerged in the form of 18-year-old Prince Ludwig of Bavaria, who was infatuated with Wagner and henceforth ensured that every courtesy and help was extended to the creative genius.

Incredibly, within the year Wagner had entered into another adulterous relationship, this time with Cosima von Bülow, wife of the conductor Hans and Liszt’s illegitimate daughter. Wagner escaped once more to Switzerland where he resumed work on Die Meistersinger, shortly before hearing the news that Minna had died.

At last, the pieces of Wagner’s haphazard life began falling into place. Cosima joined him in Lucerne with their two children, and Wagner felt a sense of contentment and fulfilment he had never experienced before.

As work on The Ring neared completion, so Wagner planned and had built at Bayreuth a theatre designed to premiere his new masterwork and bring his music to wider public attention.

On August 13 1876 the curtain rose on the very first Ring cycle at Bayreuth, and although it proved a great artistic success, financially it nearly ruined Wagner. Through a series of conducting appearances, he raised enough money to organise a second festival in 1882, marked by the premiere of his final masterwork, Parsifal. But time was running out. On February 13,1883 he suffered a massive heart attack and died in Cosima’s arms. Five days later he was laid to rest in the beautiful garden of his beloved Bayreuth villa, Wahnfried – “peace from insanity”.

THE FORCES THAT SHAPED WAGNER’S MUSIC

CULTURE

Shakespeare

The Bard’s great tragedies fuelled Wagner’s surging dramatic instincts.

Young Germany

An artistic movement that advocated a “true, warm life”.

Historicism

Notion that artistic endeavour was a natural force, with Germany at the centre.

POLITICS

French Revolution

Resulted in a wave of festivals celebrating the ‘ordinary’ man.

1848

Wagner became personally involved in a series of popular uprisings.

PEOPLE

Adolf Wagner

Wagner’s uncle saw scholarship as an entire universe to be devoured.

Theodor Weinlig

Instilled musical discipline into Wagner’s creative thinking.

Heinrich Laube

Highly influential editor of The Journal for the Elegant World.

HIS GREATEST PASSION

Women After himself and music there was one thing Wagner found totally irresistible: women. In 1836 he married a provincial actress, Minna Planer, although this didn’t prevent him from enjoying a stream of affairs (in fairness, she was hardly saintly in this regard). Things came to a head when in the mid-1850s Wagner began an adulterous affair with the poet Mathilde Wesendonck, the public outcry forcing them to flee to Venice. Just a few years later he took up with Cosima van Bülow, wife of the celebrated conductor Hans, forcing another escape, this time to Switzerland. Amazingly Wagner remained on quite good terms with both jilted husbands.

HIS MUSICAL GENIUS IN TWO BARS

Prelude from Tristan und Isolde

Following the first rehearsals for his headily sensual opera Tristan und Isolde, Wagner despaired: “This little prelude seemed so incomprehensibly new to the musicians that I had to lead them from note to note as if searching for precious stones in a mine.” And little wonder! The scoring itself must have come as a surprise, as the plaintive cello opening [A] is unexpectedly continued by the woodwind section [B]. But the real problems start in bar two with the so-called Tristan chord (F-B-D sharp-G sharp) [C], which instead of settling the music comfortably in D minor, expands it outwards into harmonic limbo.

THE ESSENTIAL WAGNER COLLECTION

The Ring of the Nibelungs

Soloists, Vienna Philharmonic/ Georg Solti

Electrifyingly paced, Georg Solti’s classic Ring cycle brings Wagner’s gargantuan epic thrillingly to life.

Decca 455 5552

Tristan and Isolde

Soloists, Royal Opera House Orchestra/Antonio Pappano

Plácido Domingo’s heart-rending Tristan is a revelation, inspiring stunning performances all round.

EMI Classics 352 4232

The Mastersinger from Nuremberg

Soloists, German Opera Orchestra/ Eugen Jochum

A gloriously radiant and heart-warming account of what is considered to be Wagner’s most treasured opera.

DG 477 7559

The Flying Dutchman

Soloists, Bayreuth Festival Orchestra/Nelson Recorded live, conductor Waldemar Nelson grabs this swashbuckling score by the scruff of the neck and never lets go for a second.

Philips 475 8289