Dmitri Shostakovich: A Life

Was Dmitri Shostakovich a stunningly original composer whose music carries the scars of political intervention, or a devoted Soviet citizen who enshrined the glory of Mother Russia in his symphonies? Whichever way you look at it, there’s certainly no sitting on the fence…

Shostakovich was the most brilliantly inventive of all Soviet composers – and the most hotly debated. Yet who was the real Shostakovich? Was he the composer of the Piano Concerto No.2’s delectable slow movement? Or the Symphony No.10’s biting cynicism? Or the gently tuneful episodes of The Gadfly film music? Or the bleak despair of the String Quartet No.15? He was all these things, of course, but how can the listener make any sense of it all?

Shostakovich’s chameleon-like creative personality makes him impossible to tie down. Take his knockabout Piano Concerto No.1, which throws virtually everything into the stylistic melting pot – vaudeville, jazz, music hall, honky-tonk, passing references to Beethoven, Haydn and Mahler, and a side-splitting finale reminiscent of Milhaud slapstick thrown in for good measure. Yet although one can never be sure just what he is going to do next, there is one immutable fact about his music – it could only be by Shostakovich.

No less controversial was the appearance in 1979 of Testimony, claimed by its author Solomon Volkov to be Shostakovich’s memoirs as told directly to him. Scholars remain divided as to the book’s veracity, yet there is a ring of truth in its basic tenet that nothing in Shostakovich’s music can be taken at face value. If Testimony is to be believed, Shostakovich’s music is a semantic minefield, laced with irony and punctuated with hollow triumphs trotted out to keep Stalin at bay.

There is one musical code we can be absolutely certain about, however: DSCH – Shostakovich’s personal musical motto. This is ingeniously derived from the German transliteration of his name: Dmitri SCHostakovich. In German musical notation, S [sounding ‘es’] is E flat and H is B natural, resulting in the eerily unsettling four-note sequence: D-E flat-C-B. This metaphor was to haunt and intensify such profoundly autobiographical works as the String Quartet No.8 and Symphony No.10.

Although Shostakovich didn’t begin formal piano lessons until he was nine, his musical studies progressed at such a phenomenal rate that within 10 years he had produced his Symphony No.1, a work of astonishing originality. The premiere took place on May 12, 1926, a date that Shostakovich henceforth celebrated as his “artistic birthday”.

The future looked rosy for the young genius. Not only was he hailed as the new hero of Russian music (Prokofiev and Rachmaninov had fled to the US several years beforehand), he was also invaluable propaganda fodder for the Soviet regime. Yet soon, his public reputation was called into question by Stalin’s “Thought Police”.

Under Stalin, all Soviet composers were required to compose music of an essentially positive nature, designed to inspire feelings of patriotism for Mother Russia. It was acceptable to express the darker side of human existence only if by the end a great victory had been won and all foes vanquished. This became the emotional blueprint for countless Russian scores during this period. Unfortunately for Shostakovich, his propensity for seeing the “dark side” in almost everything was soon to land him in hot water.

To begin with, his scathingly acerbic 1930 operatic fantasy The Nose was denounced for its “bourgeois decadence”. Although the slightly wacky Piano Concerto No.1 temporarily rescued the situation (the authorities failed to pick up on its flashing irony), things were finally brought to a head after Stalin himself attended a performance of Shostakovich’s follow-up opera, the blood-curdling Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The resulting savage mauling in Pravda (the official Soviet newspaper) speaks mountains: “This bedlam of noise quacks, grunts, growls and suffocates itself in an orgy of depravity.”

At first Shostakovich looked set to fight it out. “Sometimes the struggle for a simple language is understood somewhat superficially,” he explained in a newspaper article in April 1935. “But to speak simply doesn’t mean that one should speak as they spoke 50 to 100 years ago. This is a trap that many [Russian] composers fall into.”

Behind the scenes he was working on his Symphony No.4, whose inconsolable despair reflects his state of mind throughout this most harrowing period of his life. He got as far as attending rehearsals the day before the planned premiere when his resolve understandably crumbled. Under threat of arrest, he withdrew the work which then waited until 1961 for its Moscow premiere.

With the eyes of the State watching his every move, Shostakovich nervously set about composing a crowd-pleaser that would embrace the ideals of Stalinism without compromising his artistic integrity. The resulting Symphony No.5, with its universal message of triumph achieved out of adversity, was exactly what was needed.

Keen to keep on the right side of the State, Shostakovich then composed his First String Quartet along the Classical lines of Mozart and Haydn, marking the beginning of a cycle of 15 quartets that would rival even Beethoven’s in scope and expressive range. His Piano Quintet won the Stalin Prize in 1940, and the following year he repeated his success with the Leningrad Symphony (No.7), whose intentionally vapid and grinding repetitions went over the heads of his political masters.

For a while Shostakovich succeeded in keeping the wolves at bay, until in 1946 his neoclassical Symphony No.9 was censured for its “failure to reflect the spirit of the Soviet people”. Two years later, Stalin’s sadistic side-kick Andrei Zhdanov was on the warpath again, issuing stern warnings to several composers, including Shostakovich, about their continuing dalliance with “decadent formalism”.

Shostakovich reeled out a grovelling official apology whose insincerity must have been obvious to anyone except, apparently, the Soviet authorities: “I know the Party is right... I shall try again and again to create symphonic works close to the spirit of the people.” Privately, however, he continued railing against his existence in the chilly waters of the String Quartet No.4 and Violin Concerto No.1, both of which were returned to the drawer until more enlightened times.

It was only after Stalin’s death in 1953 that Pravda officially recanted the 1948 edict, allowing composers greater freedom to experiment. Shostakovich responded with his Symphony No.10, a vitriolic indictment of life under Stalin.

Although he continued to produce lighter music (such as the delightful Piano Concerto No.2), after the death of his wife Nina the last 20 years of his life saw his music become progressively more preoccupied with death. His Cello Concerto No.1 (1959) uses a distorted version of his DSCH motif, and the following year DSCH in its original form was pulverised into submission via the String Quartet No.8 (a work that graphically portrays his suicidal state of mind at this time).

In 1962 Shostakovich was officially censured by the authorities for the last time for his Symphony No.13, ‘Babi Yar’, whose condemnation of Soviet anti-Semitism (to words by Yevtushenko) the Soviet Premier Khrushchev found a little too close for comfort.

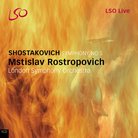

Shostakovich suffered a heart attack in 1966, after which his music became increasingly inconsolable, as is exemplified by the nerve-shreddingly claustrophobic Symphony No.14. His final string quartet consists of a series of six adagio movements whose dark despair was a direct response to the death of several close friends and the defection of his devoted colleague, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, to the West. Only in the Viola Sonata, his last completed work, does one feel a serene acceptance, as though after a lifetime of struggle against those in authority, he at last enjoyed a sense of inner peace.

Shostakovich died a broken man. The official eulogistic notice, seemingly without a hint of irony, praised him for “finding his inspiration in the reality of Soviet life, reasserting and developing in his creative imagination the arts of socialist realism and, in so doing, contributing to the universal progressive musical culture.”