On Air Now

Early Breakfast with Lucy Coward 4am - 6:30am

20 April 2021, 14:24 | Updated: 20 April 2021, 16:06

As the Austrian clarinettist slips out of the woodwind section and onto the podium for the first time in the UK, he tells Classic FM of his fluid attitude to instruments, and why it’s dangerous to see the arts as ‘non-profit’.

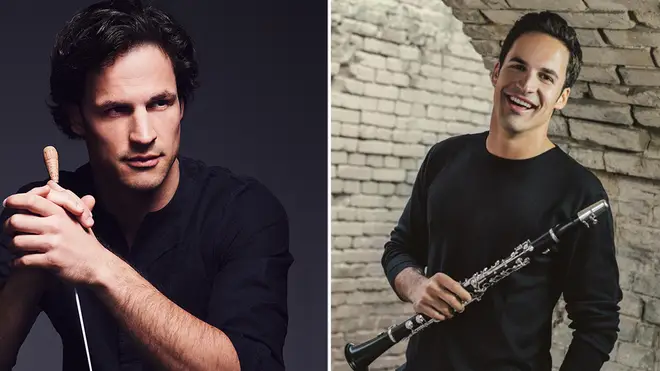

This Wednesday (21 April), Andreas Ottensamer, international soloist and principal clarinettist of the Berlin Philharmonic, is putting his reeds away and taking to the podium, to lead the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in his UK conducting debut.

It’s a move several musicians have made, including great pianist and maestro Daniel Barenboim. Ottensamer says he began the transition by ‘play-conducting’, an extraordinary balancing act coined perhaps most famously by soprano Barbara Hannigan, where the evening’s star soloist also conducts the orchestra.

“But it’s a completely different pair of shoes, to conduct a whole program as a conductor and not play an instrument,” Ottensamer tells Classic FM. “And this pandemic gave me the time to really push this to the next level and to get comfortable in myself as well.”

In a normal year, Ottensamer’s diary would be packed with both orchestral and solo engagements. But amid all the excitement, he desperately wanted “something like a year off, just to study as a conductor”.

In a strange turn of fate, his wish was granted last year as concert halls around the world began to shut their doors. While it’s been a devastating time for the arts and music, Ottensamer – along with baritone Roderick Williams, who recently signed as a composer – found a unique opportunity to focus on honing a new skill.

“The intensity that I was able to devote to conducting, and to thoroughly and substantially studying it, has been amazing throughout this period,” he adds.

Read more: Gareth Malone: ‘Singing will be a vital, national therapy for this miserable year’ >

This isn’t the first time Ottensamer’s eye has wandered through the orchestra. As a child, he took piano lessons, turning to the cello aged 10 and finally, at the comparatively vintage age of 14, finding his main instrument. It must help, when conducting, to have that deeper understanding of other sections.

“I’ve also played the cello myself, so I know how string players work, what they need. The practical side is very much embedded in my DNA,” Ottensamer says.

“But to be honest, having this insight into the two main sections, wind and strings… I’ve always been very openly fluid between instruments. I’ve never felt I’m ‘only’ a wind player or clarinettist. Even when I play the clarinet, I try to get inspiration from other instruments, like ‘okay this part sounds a bit flute-y’ or ‘I can imagine how a cellist would play that’.

“I was never very much attached to one specific instrument, even though the clarinet is of course my main instrument. That’s why I feel very natural towards all that and this transition really wasn’t a strange step at all, it was just a way to intensify my whole work in music.”

Read more: These are the 10 best clarinet works in existence >

Andreas Ottensamer plays Gershwin's Prelude No. 1

It’s been a demanding year for the arts world, with whole departments scrapped, venues closed, and in-person music-making replaced almost overnight by live-streamed concerts. Considering this is Ottensamer’s UK conducting debut, has COVID-19 complicated that initial rehearsal process with the BSO?

“This orchestra has done an incredible job in these past months,” the clarinettist emphasises. “Of course, there are huge adjustments that have to be made, with tests, the whole digital structure with cameras and lighting, and now, musicians playing at a distance from each other. The stage is probably double the size of what it used to be.”

But for Ottensamer, this is a luxury. “It’s really amazing to just be able to make music, and this is not the case everywhere else in the world at the moment. Only so many orchestras have an amazing hall, and staff around that can actually pull it off.

“If you view it like that, then all these little changes you have to make, like creating distance between players, seem really small. I can’t complain about any of this for a second.”

Ottensamer, an in-demand soloist and orchestral player, has been principal clarinet with the Berlin Philharmonic since 2011, and was Artist in Residence at the BSO, Classic FM’s Orchestra in the South of England, for a year. He must feel a sense of hope, seeing live music and live audiences finally re-emerging.

“A more fitting word would be respect – for what people can pull off when times are hard,” the clarinettist replies.

“Sometimes it comes across like ‘well if everyone was trying hard enough that we could all do this’, but that’s really not the case. Some simply can’t. And I’d much rather have a concert not take place, than if the effort really goes beyond any of the sense that it makes and it even puts people at risk. And in Bournemouth and Berlin, that has been done fantastically.”

For Ottensamer, we can learn an important lesson about the arts from this period. “Everyone very easily says ‘arts are so essential for society’ – but that doesn’t always mean that people act on it that way.

“We almost view the arts as a ‘non-profit’ kind of thing, where we say the arts are there for people for society. But in means that in times of crisis, when people get relief and joy from culture and arts, then we also need to support them.”

Even after pandemic restrictions are over, Ottensamer is sold on the idea of live-streaming – not as a replacement, but as a beneficial add-on for the classical industry.

Read more: Isata Kanneh-Mason on live-streaming: ‘You know there are invisible people watching’ >

“I think with all these digital efforts that we have made, it may seem now like ‘not quite the real thing’ if you compare it to really going to a concert. But I think for the future, these amplifications of culture and music don’t have to vanish.

“Say in Bournemouth, why not keep this structure of streaming concerts? You can reach a much wider audience with streaming – not 1,000 people, but 5,000 at one concert.”

Can, we ask, a virtual audience ever live up to the in-person experience – for either the audience or performers?

“For sure it will be amazing again when we play for a full house. It’s like if you don't eat sugar for a year, and then suddenly you eat an entire candy bar and go over the top with everything you do on stage. So that will be something amazing to witness – I can’t remember the last time that happened.

“The atmosphere is really at its peak when the house is full, and that collective experience is so important for both the audience and performers.”

Watch Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra’s live-streamed concert conducted by Andreas Ottensamer and presented by Classic FM’s Catherine Bott, on the BSO website.