The Podiums And Pianos Of Vladimir Ashkenazy

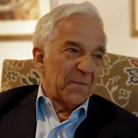

A talented and versatile musician, with a charming and generous personality, Vladimir Ashkenazy is equally at home in front of an orchestra as on a piano stool – and equally adored when at either.

During their first rehearsal, the musicians of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, who have never worked with Vladimir Ashkenazy before, will – out of respect – call him “Maestro”. By the second rehearsal, they will switch effortlessly to “Vova”, the Russian diminutive of Vladimir, which suits him so much better.

Ashkenazy, the RLPO’s first Artist Laureate (alongside Simon Rattle), will be working with the orchestra on its programme for Liverpool’s year as European Capital Of Culture. Lucky Liverpool. Ashkenazy is one of the great ambassadors for classical music. He is also one of the nicest. Maestro, and all the negative baggage from Toscanini to Karajan that comes with it, doesn’t suit him at all.

“Excuse me a moment,” he apologises, when we meet after a rehearsal with the Philharmonia. “I need to change my shirt. Then we can have tea.” Five minutes later, Ashkenazy is waiting in line with his tray, chatting to the musicians. I’m surprised that he doesn’t have someone to bring him his tea. “Not at all,” he protests. “I’m no different from anyone else.”

This is definitely not maestro behaviour.

“Perhaps it’s just that we instrumentalists have a particular empathy with the players, which makes us more collegial conductors,” he says.

Ashkenazy is a brilliant pianist and conductor, so surely that makes him special?

“Absolutely not. I’m often asked if I’m a pianist or a conductor, but I just call myself a musician. It’s impossible to say which activity informs the other. Everything is a constant process. The laws of music are the same if you play the violin, the piano, or if you conduct an orchestra.

“The conductor acquires a skill to do with communicating with the hands, arms and eyes; and the instrumentalist had better know how to produce the notes to the highest level, because if you can’t then nobody needs you. Talent, technique, understanding, communication – you need all that, but the rest is in the hands of God.”

I ask if he is a religious man. Ashkenazy’s reply is thoughtful.

“I don’t practise a particular religion, but if by religion you mean believing in something, then yes, I feel strongly about lots of principles you find in the Bible or in many religious books. They are principles to do with consideration for people, love and a sense of honesty. And I believe that one should do one’s best not to be greedy or aggressive.”

His consideration for others is clear to see. A few years ago, he was conducting a Scandinavian orchestra in a piece they were unfamiliar with.

“In rehearsal, one of the oboists couldn’t get the note. I felt so bad for her. ‘Don’t worry if it doesn’t come,’ I told her. ‘I’ll wait a bit and give you time. Just relax. Whatever happens, I’ll be with you.’ In the end they played very well. Afterwards, she came up and hugged me and said, ‘You make us feel so comfortable.’ But it’s the duty of the conductor to make each member of the orchestra feel comfortable, or else how can they play?”

Ashkenazy was born in Gorky in 1937. He started out as a pianist and, having studied in Moscow, went on to win prizes at the Warsaw International Chopin Competition (1955), the Queen Elisabeth Competition (1956) and the Tchaikovsky Competition (1962). In 1963, at the height of his State-sponsored fame, he left Russia and defected to the West.

There is an extraordinary symmetry about his new appointment with the RLPO. He announced his defection at a press conference, which was held at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool. When he began conducting, the first symphony orchestra he worked with was the RLPO.

“So I have a long history with them, although I don’t have a relationship yet with the current musicians because I haven’t conducted the RLPO for 20 years. All the players are new to me, but I have heard that they are very talented. I am delighted about my new association and very much looking forward to working with them.”

We discuss the intensity of orchestral relationships – how, for a short time, the conductor and players become like a family, then the performance is over and you have to say goodbye.

“It’s like that miserable playwright Strindberg,” he jokes. “Strindberg said about the woman he was in love with, ‘the intensity of parting is only compared with the joy of seeing you again’. For me, when a concert has gone well, the sadness of leaving is sustained by knowing that there is a plan to come back.”

Andrew Cornall, the RLPO’s executive director, is the man who brought Ashkenazy back to Liverpool. Cornall has known Ashkenazy for almost 30 years – both as a pianist and as a conductor.

“Vova is a wonderful musician and human being. He has no airs or graces and is a delight to be around,” he says. “The music is never about him, because he is the essence of what it means to capture the collaborative spirit of music-making. That’s a very special quality. The orchestra was thrilled when he accepted its invitation.

“And our audience is in for a treat. They are loyal, enthusiastic and numbers are increasing, but many of our supporters haven’t had the opportunity to experience Vova conduct a concert, or to hear him live in recital. Now they can experience a truly great musician drawing music from 75 people in his own way.”

For Ashkenazy’s first concert in November, he will conduct works by Sibelius and Rachmaninov. Two days later, he’ll play the piano in recital with his son Vovka, himself an acclaimed pianist. Talking to Ashkenazy, you can’t help but be inspired by his humanity and generosity of spirit. He enthuses about Daniel Barenboim and Valery Gergiev and is optimistic about the future of classical music.

“Maybe it will be limited for a while and then it will grow again. Music is an expression of our internal world with all the rainbow of our feelings. I am sure we will sustain it in some way. As for my own music-making – I have some gifts but I’m not the greatest in the world. All I can do is my best.”