Why are orchestras arranged the way they are?

9 April 2024, 16:21

Why are the violins always at the front, with winds behind? And why will you almost never find the tubas sat right next to the conductor?

Listen to this article

At most orchestral concerts today, you’ll see the violins directly to the left of the conductor, with violas centre left and woodwind, then percussion, behind. To the right of the conductor, you’ll find the cellos and double basses, with the brass section behind them.

Loud winds and percussion at the back, and quieter strings at the front, seems a logical set-up. But a little over 100 years ago, this formation didn’t exist…

The second violin section, rather than sitting next to the first violins, used to be seated opposite, where you’d find the cello section in most orchestras today.

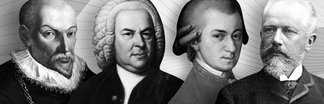

This seating plan helped support the ‘antiphonal’, or conversational, effect in the strings, which 18th and 19th-century composers like Mozart, Elgar and Mahler often wrote into their music. Listen out for it in the finale to Mozart’s ‘Jupiter’ Symphony No. 41:

Mozart: Symphony No. 41 Jupiter | Hartmut Haenchen & Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Chamber Orchestra

Some composers of the 19th and 20th century specified orchestral layouts for their works.

In two movements of his Requiem, Hector Berlioz indicated that brass instruments should be placed at all four corners of the hall. And in many performances of Gustav Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ Symphony No.2, a small ensemble of French horns, trumpets and percussion will play offstage in an upstairs gallery or similarly striking spot.

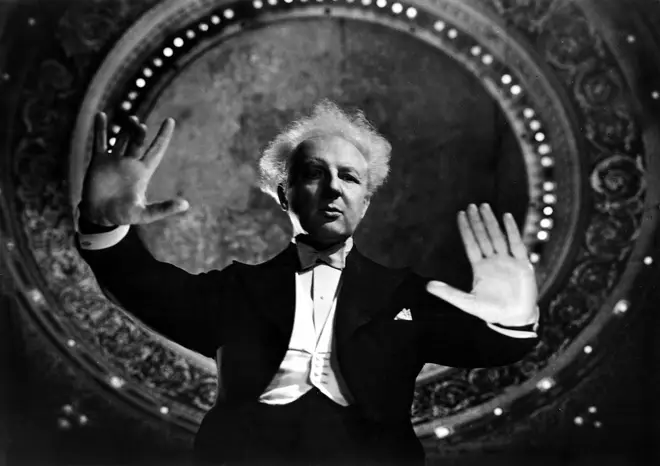

Then in the early to mid-20th century Leopold Stokowski, best known for conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra and leading all the music for Disney’s 1940 animation Fantasia, came along and changed the game for good.

Stokowski felt that the previous layout didn’t provide the best sound blend and projection, so he radically experimented with different seating plans.

Music director of the Jacksonville Symphony Orchestra, Courtney Lewis, recalls: “On one occasion, he horrified Philadelphians by placing the winds and brass in front of the strings. The board was outraged, arguing that the winds ‘weren’t busy enough to put on a good show’.”

To the board’s point, the winds aren’t always on the melody and they often have several consecutive bars of rest, unlike the violin section.

“But in the 1920s he made one change that stuck,” Lewis continues. “He arranged the strings from high to low, left to right, arguing that placing all the violins together helped the musicians to hear one another better.

“The ‘Stokowski Shift’, as it became known, was adopted by orchestras all over America.”

Read more: Why do orchestras have so many violins?

For acoustical reasons, having the violins together at the front makes sense. An orchestra has 20 violins and two tubas because tubas are a lot louder than violins, so with the same logic, violins are usually positioned on the frontline of an orchestra so they can be heard.

Violins have a bright, singing tone that makes them well-suited to playing melody lines, with the lower pitched instruments playing the harmony underneath. This set-up achieves a balanced sound that is projected out to the hall, with plenty of resonance coming from those string instruments.

There’s also something to be said for the visual beauty of putting violins at the front. The sweeping motion of 20 violin bows moving together in unison, with plenty of fast fingerwork on display, is rather striking.

The Stokowski shift isn’t strictly the orchestra’s final form. Many of today’s conductors and ensembles like to experiment with new and innovative ways to perform live music.

Today, the Aurora Orchestra are pioneering with their immersive concerts, where players are boosted onto platforms allowing audiences to walk inside the orchestra – a particularly electrifying experience.

Italian conductor Riccardo Muti enjoys playing around with on-stage layout, notably in performances of Bruckner symphonies. And of course, pit orchestras in operas and musical theatre productions have various different seating set-ups.

But really, since Stokowski’s day, one thing that has stuck is those sweeping strings at the front.

Perhaps it will be a while then, before we see the tubas take a place in the spotlight. Just don’t forget to bring your earplugs, when they do…