Discovering The Great Composers - Mussorgsky

Blessed with a fantastical imagination, yet cursed with a predilection for alcohol, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky was the archetypal tortured genius.

Mussorgsky was one of music’s great originals. Everything he composed was conceived in terms of the natural rhythms, melodies and harmonies of Slavonic folk music. He constantly railed against tradition, honing his music in order to make it, in his words, “an artistic reproduction of human speech in all its finest shades”.

Like Janácˇek, his psychological insight into the dark side of human nature led him into regions of expression hitherto undreamed of. However, his lack of solid technique and his increasing reliance on vast quantities of spirits ultimately proved insurmountable. Rimsky-Korsakov once joked that Mussorgsky would “trans-cognac” himself to death – a light-hearted aside which in the event proved tragically prophetic.

Mussorgsky’s natural talent was obvious from the start. Initially taught by his mother he became a pianist prodigy, making his debut at just nine-years-old. Four years later, in 1852, he enrolled at the Imperial Guard’s cadet school and composed the Porte-En-Seigne Polka, a surprisingly cheery piano miniature.

In 1857, Dargomïzhsky, one of the first Russian nationalist composers, introduced him to fellow composers Cui and Balakirev, and Mussorgsky resolved to devote himself to music. He was encouraged by Vladimir Stasov, the champion of Russian music, who dubbed the new generation of St Petersburg composers the "Moguchaya Kutchka" or "Mighty Handful".

At first Balakirev was happy to try and instil some discipline into his unruly pupil. Yet it became increasingly obvious that Mussorgsky – already prone to the severe mood swings that would plague him throughout his life – was totally incapable of sustaining a rigorous training. In despair, Balakirev (a far from stable personality himself) dismissed his genius pupil as “almost an idiot”.

In 1863, a shortage of funds forced Mussorgsky to take a job as a clerk in the civil service. Though brimful of startlingly original ideas, the pieces he composed in his spare time often lacked any musical logic. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for Rimsky-Korsakov’s later kindness and support Mussorgsky, and his music, might have fallen by the wayside.

According to Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky’s music was blighted by “absurd, disconnected harmony, ugly part-writing, sometimes strikingly illogical modulations, sometimes a depressing lack of them”.

Borodin reported to his wife in a letter: “Korsinska [Rimsky] has smoothed over all Modest’s rough harmonic edges, his pretentiousness in orchestration, his lack of logic in the construction of musical form – in a word, he has made his pieces incomparably more musical.” As a result, for many years, it was largely through Rimsky-Korsakov’s well-meaning, highly polished revisions that Mussorgsky’s music gained a wider audience.

One of these pieces was Mussorgsky’s operatic masterwork, Boris Godunov, in which he attempted to “view the people as one giant being, inspired by one idea”.

Mussorgsky’s original version of Boris possesses a raw intensity that Rimsky-Korsakov’s sophisticated rewrite patently lacks; in the case of Mussorgsky’s next major work, though, A Night On The Bare Mountain, Rimsky-Korsakov’s editing was almost all to the good.

Something of the flavour of the fantastic and macabre orchestral invention can be gathered from the preface to the Rimsky-Korsakov edition: “The noise of the underworld composed of ghosts’ voices – appearance of the spirits of Hell, finally of Satan himself – worship of Satan, black mass and witches’ Sabbath. At the climax of the orgy, the bell of a far-off village church is heard; the spirits flee asunder. The day dawns.”

Throughout the 1870s, Mussorgsky became increasingly prone to epileptic seizures, and his predilection for alcohol quickly developed into full-blown dependency.

Rimsky-Korsakov, in his memoirs, places the blame for Mussorgsky’s rapid decline squarely on the shoulders of Boris Godunov. Its early success led Mussorgsky to believe he was capable of almost anything and its subsequent critical mauling turned him to drink, as he had neither the inclination nor the technique to do anything about it. In a letter to Stasov, Mussorgsky frankly admitted: “Maybe I’m afraid of technique because I am poor at it.”

Yet whatever Mussorgsky lacked in terms of formal conservatoire training, he more than made up for with the blazing quality of his ideas. His exuberantly inventive song cycle The Nursery (1870-72) created such a stir that Franz Liszt suggested the two men should meet; the moody Russian refused to have anything to do with him.

Two years later, Mussorgsky produced his most celebrated work, Pictures At An Exhibition. Borodin, who was present at the private premiere given by the composer, recalled that after Mussorgsky had finished pummelling the piano, they discovered that several of the felted hammers had buckled irreparably under the pressure.

Pictures At An Exhibition departs from convention at almost every turn. By way of a series of interludes, the composer himself regularly appears in the form of a recurring Promenade theme.

As he strolls around the gallery, stopping at each new stage design or watercolour by his friend Viktor Hartmann, the Promenade transforms; sometimes settling us down for the next picture, occasionally creating a startling change of atmosphere.

From the bustling scene of French women quarrelling in the Market Place At Limoges, to the chilling portrayal of Paris’s Catacombe, to the Great Gate At Kiev with its panoply of cascading octaves suggesting the pealing of bells, Mussorgsky’s inspiration doesn’t falter.

There followed two song cycles set to unremittingly gloomy texts by another of Mussorgsky’s close friends, Count Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov, Sunless (1874) and Songs And Dances Of Death (1875-77); the song cycles are among the bleakest expressions of the human condition.

The ever-supportive Borodin – then working on his epic opera Prince Igor – was proud to accompany Mussorgsky in his latest desolate masterpieces, but both Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov tried to sweeten the bitter pill of Songs And Dances Of Death with colourful, piquant orchestrations of Mussorgsky’s unforgiving piano accompaniments. Nowadays, it is Shostakovich’s sparse, haunting and unmistakably Russian orchestration that is considered the most authentic.

By now Mussorgsky was physically and mentally wracked by alcohol abuse. However, the ailing composer spent part of 1879-80 on tour accompanying an old contralto friend, Darya Leonova, and there were even signs that he was trying to conquer his alcoholism – but sadly it was a case of too little, too late.

His opera Khovanshchina (1872-80) was tantalisingly complete in every detail in his imagination – Borodin even sat with him as he gave a complete performance of the work at the piano. Yet by 1880 he was simply incapable of getting his ideas down in cogent form on manuscript. It was left to Rimsky-Korsakov and Shostakovich to prepare performable editions from Mussorgsky’s rambling sketches.

Mussorgsky’s ideas for another abandoned opera, The Fair At Sorochintsï (1874-80), whose first and final acts Rimsky-Korsakov described as having “no real scenario or text, save musical fragments and characterisations”, were later cobbled together by Lyadov and Nikolay Tcherepnin.

In February 1881, suffering from constant debilitating fits, Mussorgsky finally went over the edge and informed Leonova, according to her account, “that there was nothing left for him but to go and beg in the streets”.

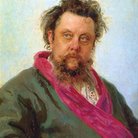

Painted shortly before Mussorgsky’s death, Ilya Repin’s famous portrait is one of the most heartrending likenesses of any composer – bloated, bulbous-nosed, red-faced and windswept; it is impossible to imagine that such a physical wreck had been renowned in his youth as something of a dandy. He died of a heart condition brought about by chronic alcoholism days after his 42nd birthday.

Russian musicologist Igor Glebov effectively summed up Mussorgsky’s creative problems in a 1930 treatise: “His greatest misfortune was that he came into the world half a century too early. The technique he would have required in order to achieve his ends had not yet come into being.”

In his essential aims, however, Mussorgsky succeeded triumphantly, as he so eloquently put it: “Life, wherever it is shown; truth, however bitter; speaking out boldly, frankly, point-blank to men – that is my aim. I am a realist in the highest sense – my business is to portray the soul of man in all its profundity.”