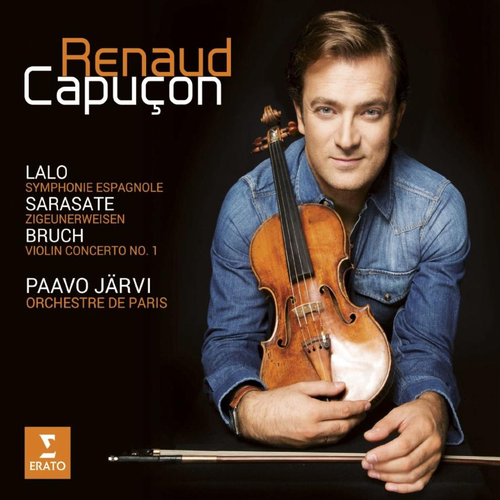

The Story Of Max Bruch's First Violin Concerto

You would think, listening to the world’s most popular violin concerto, that it had been written in a white-hot spurt of inspiration. Well, think again! Max Bruch’s beloved First Violin Concerto had a prolonged gestation and a difficult birth.

The composer’s opera Die Loreley had already been produced, as had his first significant choral works, by the time the 26-year-old composer began work on the concerto in the summer of 1864.

Nearly 18 months later he wrote to his former teacher Ferdinand Hiller: “My violin concerto is progressing slowly – I do not feel sure of my feet on this terrain. Do you think that it is very audacious to write a violin concerto?” A first version, completed by the beginning of 1866, was withdrawn by the composer after a single performance on 24 April.

Dissatisfied, Bruch sent the manuscript to the great virtuoso Joseph Joachim for his comments. Joachim replied with a detailed list of proposals for the work’s improvement (some of which were taken up) to which Bruch responded with a list of diffident queries and suggestions.

He later forbade the publication of this last letter fearing that it would make him seem too dependent on Joachim for the composition. Still insecure about his work, Bruch then sent the score to his conductor friend Hermann Levi and the composer and violinist Ferdinand David for their comments (David had advised Mendelssohn on his Violin Concerto in E minor two decades earlier and had given its first performance).

At last, having been rewritten, in Bruch’s words, “at least half a dozen times”, the concerto was completed to his satisfaction and given its first performance in its final and definitive version on January 7, 1868 in Bremen with Karl Reinthaler as conductor and Joachim as soloist.

The score’s manuscript bears the dedication “Joseph Joachim in Verehrung zugeeignet", though the word “Verehrung” (respect) was crossed out by Joachim and substituted by “Freundschaft” (friendship).

The concerto was quickly taken up by all the great violinists of the day and played so often that it overshadowed everything else Bruch wrote. In the end, he could not bear to hear it. To cap it all, he had sold the work outright to the publisher Cranz and so made no more money out of his biggest hit.