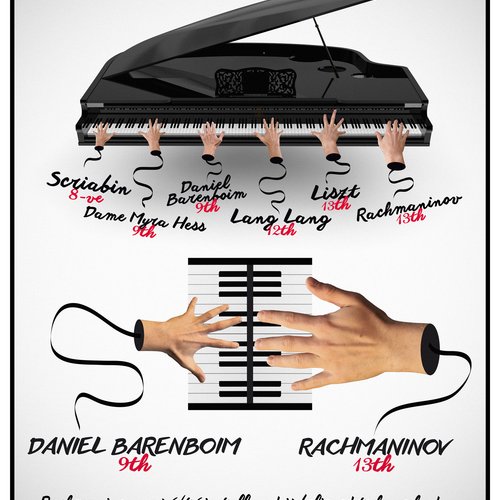

Inside The Mind Of Daniel Barenboim

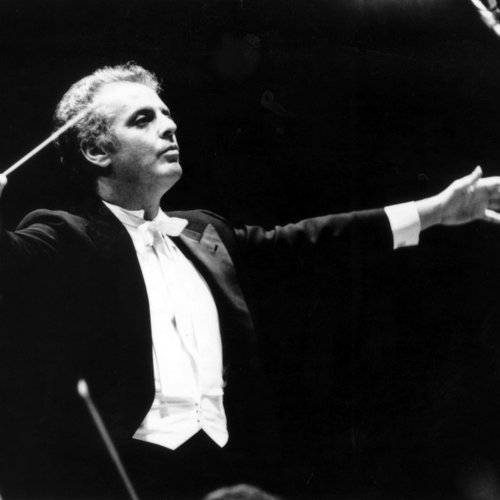

Daniel Barenboim is busier than ever. The world-class conductor, brilliant pianist and campaigner for Middle-Eastern peace through the revolutionary East-West Divan Orchestra is in New York on the eve of a momentous concert reuniting him with the New York Philharmonic, an orchestra he hasn’t played with for some 15 years.

On top of that, he’s just flown in from Munich where he had been conducting his very own Berlin Staatskapelle in a Brahms symphony cycle. And only the previous week, maestro Barenboim completed an eight-concert performance of all Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas in Vienna.

Oh, and let’s not forget the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, where he’s artistic director. His life is hectic, his staple music hot-blooded and romantic. A world apart from his most recent solo piano disc: the private, intensely personal world of Book I of JS Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, a repertoire choice that will take his fans completely by surprise.

Or will it? The performance turns out to be thrilling – surprising but thrilling. There’s no concession to authenticity as he rides the preludes with breathtaking orchestral scope and caresses the fugues with all the resources the piano can muster. His huge emotional range owes much to legends Edwin Fischer and Wanda Landowska, two Bach giants he cites as influences.

“I think the orchestral conception of Landowska on this huge Pleyel harpsichord is wonderful. I love it. She was such a formidable personality. The grandeur of Landowska – unequal for me in Bach, unequal! And Fischer had a luminosity of sound. I can’t describe it any other way. Some of the soft playing was wonderfully round and mellow.”

Barenboim’s recording betrays an air of someone who has lived with these works all his life. He has. Through Bach, Barenboim, one of the world’s true music heroes, is returning to his roots.

“For me, playing Bach is like going back to my beginnings,” he reveals through the thick cloud of a Cuban cigar. “I grew up on Bach. I played so much of it when I was a child, you know. My father really taught me to play Bach and then I went to study with Nadia Boulanger. In my first lesson with her I was 12. She was probably as old as I am now [62] but she seemed as old as the hills to a 12-year-old – dry lips, dry fingertips. She put a prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier on the stand and said, pointing to the prelude in E-flat minor, ‘You will play me this in A minor!’ She had a wooden ruler in her hand and when I played a wrong note she would gently rap my fingers.”

So why has it taken him, in effect, 50 years to record these masterpieces? Barenboim certainly hasn’t shied away from some of the most difficult piano repertoire in the past. His performances with his former wife, the cellist Jacqueline du Pré, are the stuff of dreams – listen to their Trout Quintet on Teldec and witness some of the greatest chamber playing in history. The complete Beethoven piano sonata cycle recorded in his early 20s leaves the listener dazed and startled by its sheer spontaneity. And the Mozart piano concertos recorded between 1967 and 1974 with the English Chamber Orchestra betray a youthful energy rare in most other recordings.

But Barenboim treats JS Bach differently, almost reverentially.

“It took me 25 years to finally record the Goldberg Variations. And it’s right. It’s a major step – the Goldbergs or the 48 is music that is sufficient for a whole lifetime. I felt I wanted to do the Well-Tempered when I was ready. The music has to do with the very depth of human existence. When playing this music, you have to unite mind, heart and stomach – analysis, emotion and temperament.”

For Barenboim, staying away from Bach also has much to do with public taste as anything else.

“For the last 20 or 30 years, it was out of fashion to play Bach on the piano. I remember having a conversation with Claudio Arrau in his 70s or 80s and he said, ‘I don’t think I can play Bach on the piano anymore.’ But then he changed his mind. One of his last recordings was the Bach Partitas on the piano.”

In 2000 Daniel Barenboim celebrated 50 years of public performance with a piano recital at the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires. Now he wants to make more time for the instrument and in 2006, he is stepping down as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra after 15 years.

“I would like to play more piano and I would like to play a greater variety of repertoire,” he explains. And Barenboim freely admits that he’ll be at his happiest when he conducts the New York Philharmonic from the keyboard in Mozart the following evening.

“The sheer pleasure of being able to play and communicate with them through the piano is for me essential. At the rehearsal I enjoyed myself so much.”

So is this the start of a quieter life?

Barenboim scowls: “I’m not slowing down – I’m just going to work in different ways. I’m anything but tired and I’m full of ideas. I feel this recording is a document of what I can do now: good, bad, mediocre, great, whatever. Are there a million things I could add to the performances? Absolutely.”

As they say, geniuses are the first to find fault in themselves.